Mental Health Counseling for Diabetes Patients

Since the beginnings of modern medicine, experts have recognized a connection between diabetes and mental illness.

Since the beginnings of modern medicine, experts have recognized a connection between diabetes and mental illness. In the early 1800s, Thomas Willis, an English neurologist, speculated that diabetes was caused by “long sorrow and other depressions.”1About 70 years later, British psychiatrist Sir Henry Maudsley wrote in his bookThe Pathology of Mind, “Diabetes is a disease which often shows itself in families in which insanity prevails.”1More recently in the 1940s and 1950s, psychiatrists used insulin-coma therapy to treat patients with schizophrenia.2

Today, scientists understand a bidirectional relationship between psychiatric disorders and diabetes: each influences the other in a variety of ways. This article attempts to elucidate the prevalence of these often comorbid conditions and discuss the interface between diabetes and alcohol abuse, major depression, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia, respectively.

Co-occurrence of Diabetes and Psychiatric Disorders

This presents in 5 different patterns1:

- Both can occur as independent conditions with no apparent connections;

- Diabetes can be complicated by the emergence of a psychiatric condition;

- Specific psychiatric disorders increase the risk of developing diabetes;

- Hypoglycemic and ketoacidosis episodes present with psychiatric symptoms; and,

- Diabetes can result as a side effect of psychiatric medications.

When diabetes and psychiatric conditions co-occur, treatment outcomes decline through impaired quality of life, reduced patient adherence, increased emergency room visits, higher rates of hospitalizations, and increased cost of care. A 2009 study found that the cost of care actually doubles in patients with co-occurring diabetes and mental health conditions compared with those who only have 1 of the 2 illnesses.3

Primary care providers are often unaware of the possible co-occurrence of psychiatric conditions in their diabetes patients. In fact, around 45% of psychiatric disorders go undiagnosed in patients treated for diabetes.4Experts recommend that clinicians screen all patients with diabetes for psychological distress using either the patient health questionnaire (PHQ) or other standardized assessment. The PHQ is a well-validated 9- or 15-question self-report questionnaire.5

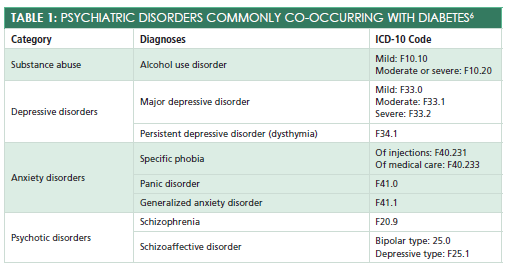

Psychiatric disorders are typically diagnosed using theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, and coded using the ICD-10.6Codes for psychiatric disorders are found in chapter F and categories 00-09.Table 16lists the categories of psychiatric disorders commonly seen co-occurring with diabetes.

Alcohol Abuse

About 50% to 60% of patients diagnosed with diabetes also consume alcohol.7Even when consumed safely, alcohol use increases a diabetic individual’s risk of hypoglycemia. Alcohol can impair an individual’s ability to recognize and respond effectively to a diabetic emergency, such as ketoacidosis. Both alcohol misuse and diabetes independently cause peripheral neuropathy and retinopathy, resulting in synergistic effects for both complications. Long-term alcohol use can lead to excessive weight gain further exasperating diabetes, as well.7

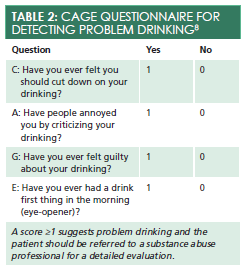

The CAGE questionnaire is a brief 4-question tool to help screen patients for problem drinking (Table 28). If patients answer “Yes” to more than one question, they should be referred to a substance abuse professional for a detailed evaluation. Primary care providers can offer the patient a referral and provide a brief intervention in the form of motivational interviewing, a patient-centered yet direct method for increasing intrinsic motivation by exploring and resolving patient ambivalence.9Primary care providers can use one simple MI tool in their practice: OARS (open-ended questions, affirming, reflective listening, and summarizing).9Remembering this acronym can help providers focus their therapeutic communication and encourage the patient to seek additional treatment.

Major Depressive Disorder

This is the most common psychiatric condition in patients with diabetes. In fact, its prevalence is 2 or 3 times higher in those with diabetes than in members of the general population.10Unfortunately, the exact relationship between these 2 conditions remains uncertain. Hyperglycemia worsens during periods of depression, and it actually exacerbates and prolongs any depressive state.1Moreover, long-term use of high-dose antidepressant medications doubles a patient’s risk of developing diabetes later in life.1

At each appointment, primary care providers should conduct a brief risk assessment using the PHQ-2 (Table 311). With this 2-question tool, clinicians can quickly determine the need for a mental health referral. A score greater than or equal to 3 indicates a need for further investigation, as well as a referral to a mental health professional, such as a psychiatric nurse practitioner or psychologist. Depending on the severity and type of depression, mental health professionals will likely use a combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapy as treatment.11

Anxiety Disorders

The prevalence of these is higher in patients with diabetes than in members of the general population. The prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder, for example, is 3 times higher for those with diabetes.12Research has also demonstrated that symptoms of anxiety increase an individual’s risk of developing diabetes later in life. Needle-and-injection—related phobias, as well as a phobia of a hypoglycemic episode, are also sometimes found in patients with diabetes.13

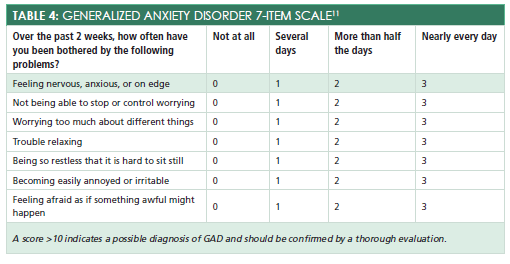

To screen for generalized anxiety disorder, primary care providers can use the GAD-7 scale, a 7-item self-report questionnaire (Table 411). A score of greater than or equal to 10 indicates a possible diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder and should be confirmed by a thorough evaluation. Phobias are characterized by a persistent, disproportional fear of a specific object or situation such as needles or a hypoglycemic episode.2Psychological treatments for anxiety disorders are extremely effective; therefore, a referral to a mental health clinician will likely substantially improve the patient’s quality of life.2

Schizophrenia

For those with schizophrenia, the risk of developing diabetes is 4 times greater than for members of the general population.14Individuals with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes have higher mortality rates than those who only have one condition, and a family history of diabetes is more common in those with schizophrenia than those without.14

Research reveals that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the high rate of impaired glucose tolerance in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.1Inactivity, poor nutrition, and treatment with antipsychotic medications increase the risk of developing diabetes later in life.1Clozapine and olanzapine are most likely to cause metabolic syndrome, followed by risperidone and quetiapine.2There is also some evidence suggesting that schizophrenia is an independent risk factor for diabetes.1

Managing patients with both a psychotic disorder and diabetes requires expert care coordination between primary care and mental health providers.2Primary care clinicians should recommend psychological approaches that will help their patients understand and remain adherent to their diabetes treatment plans. Maintaining close contact with the patients’ case managers and reinforcing self-management strategies at each appointment can help improve this population’s outcomes.

Referral to a Mental Health Professional

This may make a patient feel stigmatized or “crazy.” Even patients who are interested in professional counseling face significant barriers including cost and time commitment. The most successful referrals occur within a trusting and established patient-provider relationship.

Knowing when to refer a patient with diabetes can also be difficult. Referrals can be made for a psychiatric nurse practitioner who specializes in psychotropic medication management or for a psychologist with advanced training in a particular form of psychotherapy, such as motivational interviewing or cognitive-behavioral therapy. Referrals to psychiatric specialists should almost always be provided in the following cases:

- Patients taking multiple psychiatric medications who are not responding to a new medication;

- Patients who express suicidal ideation or demonstrate chronic suicidal tendencies;

- Patients with multiple psychosocial problems;

- Patients who desire help adjusting to a new acute or chronic illness;

- Patients with multiple somatic complaints without discernable evidence of a physical cause; and,

- Patients who need extra help with health behavior change (eg, tobacco cessations and weight loss).11

Conclusion

The interface between diabetes and psychiatric disorders is complex and not completely understood. This comorbidity often increases the risk of poor patient outcomes; however, when primary care providers and psychiatric specialists work together, these individuals can receive effective and comprehensive treatment.

Dr. Melissa DeCapua is a board-certified psychiatric nurse practitioner. She currently works as a consultant for small health care technology companies, and she recently won the Seattle Health Innovator award. Dr. DeCapua is a strong advocate for empowering nurses, and she fiercely believes that nurses should play a pivotal role in shaping modern health care. For more about Dr. DeCapua, visit her website atmelissadecapua.comand follow her on Twitter@melissadecapua.

References

- Balhara YP. Diabetes and psychiatric disorders.Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15(4):274-283. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85579.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock, VA, Ruiz P.Synopsis of psychiatry.11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Centorrino F, Mark TL, Talamo A, Oh K, Chang J. Health and economic burden of metabolic comorbidity among individuals with bipolar disorder.J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(6):595-600. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181bef8a6.

- Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Balluz LS, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. Undertreatment of mental health problems in adults with diagnosed diabetes and serious psychological distress: the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2007.Diabetes Care. 2010;33(5):1061-1064. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1515.

- Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella, K. Validity of the patient health questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people.J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(4):596-602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x.

- American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.5th ed.Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Ghitza UE, Wu LT, Tai B. Integrating substance abuse care with community diabetes care: implications for research and clinical practice. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2013;4:3-10. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S39982.

- Dhalla S, Kopec JA. The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: a review of reliability and validity studies. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(1):33-41.

- Arkowitz H, Westra HA, Miller WR, Rollnick S.Motivational interview in the treatment of psychological problems. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008.

- Engum A. The role of depression and anxiety in onset of diabetes in a large population-based study.J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(1):31-38.

- Greenberg T.The psychological impact of acute and chronic illness: A practical guide for primary care physicians. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2007.

- Huang CJ, Chiu HC, Lee MH, Wang SY. Prevalence and incidence of anxiety disorders in diabetic patients: a national population-based cohort study.Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(1):8-15. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.008.

- Green L, Feher M, & Catalan J. Fears and phobias in people with diabetes.Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16(4):287-293.

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J, Whyte S, Penny C. Effects of severe mental illness on survival of people with diabetes. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(4):272-277. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074674.