A Comprehensive Guide to Diabetic Foot Exams

An individual living with diabetes has a 25% chance of developing a diabetic ulceration on their feet over their lifetime.

Diabetes is a chronic disease process defined as a hyperglycemic state that can affect individuals of any demographic type and across the lifespan. This hyperglycemic state is precipitated by the body’s lack of insulin response, whether from a decreased production of insulin or the body’s inability to productively use the insulin that the pancreas creates. Over time, the sustained levels of hyperglycemia related to uncontrolled diabetes have a negative effect on the body and can result in serious life-long complications, some of which may lead to death. As health care providers, we are not only responsible for the diagnosis and treatment of our patients’ medical conditions, but we should also be educating them on how to properly care for themselves to ensure there are little to no sustained and continued complications.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is the result of an autoimmune response where a breakdown of the beta cells in the pancreas causes an insufficient amount of circulating insulin. This decrease (and often cessation) in the amount of circulating insulin requires the daily administration of insulin. Patients who present with T1D frequently have only been experiencing symptoms for a short duration of time. Typical onset occurs in patients who are younger than 30 years, and is not as common as its counterpart, type 2 diabetes (T2D).

T2D develops when the pancreas produces an inadequate amount of insulin because of insulin resistance—the result of the body’s cells’ inability to properly respond to the insulin level produced, causing an increase in the level of circulating glucose in the body. Patients usually have a slow onset of symptoms, which can last years before a T2D diagnosis. A disease process that once used to affect primarily older adults, T2D is now being diagnosed in children as well.

An individual living with diabetes has a 25% chance of developing a diabetic ulceration on their feet over their lifetime.1The following are the essential elements of the diabetic foot exam.

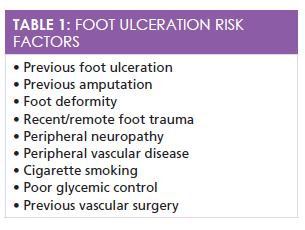

Discussing and evaluating a few key elements can assist in preventing foot ulcerations. Taking an in-depth history is an important, necessary component of any patient interview, but it cannot be the sole basis for a diagnosis and risk examination. The past medical history can reveal red flags that the provider can note for the upcoming physical examination. For example, a previous ulceration or amputation places the patient at a higher risk for developing another ulcer. Additional risk factors for foot ulceration are listed inTable 1in no particular order. A discussion of any symptomatology the patient is experiencing is warranted and should include any neuropathic and vascular complications.

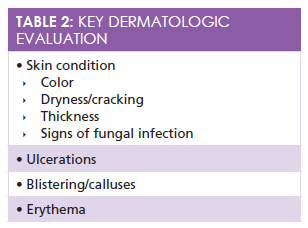

A thorough physical examination should always begin with a visual inspection of the patient in a well-lit, private room. The patient should remove socks and shoes prior to the examination. Ill-fitting footwear can cause deformities and are a common cause of foot ulceration development. Inappropriate footwear can include shoes that are an incorrect size inclusive of width, length, height, and the toe-box size. Patients whose shoes are excessively worn should be encouraged to obtain newer, well-fitting footwear because excessively worn shoes do not provide enough support for the diabetic foot. Evaluating the dermatologic state of the skin is imperative;Table 2highlights key features. A visual evaluation of the musculoskeletal foot frame should ensure there are no deformities or muscle wasting.1Patients should be taught how to inspect their foot daily, and if they find any concerning sores, ulcerations, or damaged areas, they should be evaluated by their medical provider.

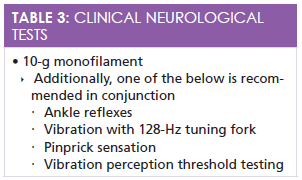

One of the leading precipitating factors in the most frequent triad of foot ulceration causes is peripheral neuropathy. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the detection of loss of protective sensation (LOPS) is now the most recommended method for clinical examination versus evaluating for early neuropathy.1The LOPS examination consists of a combination of 5 different tests, is uncomplicated, and there is no costly equipment necessary to be thorough. Although only one of the 5 tests needs to be completed annually, best practice indicates that using a 10-g monofilament and any of the additional tests (Table 3) is more comprehensive. Two normal tests indicate that the patient is not currently suffering from LOPS, whereas one or more abnormal tests indicate the presence of LOPS.

10-g Monofilaments

Used worldwide,1this test detects a loss of pressure sensation when the monofilament is placed onto the plantar surface of the foot and pressure is applied. Subsequently, the pressure causes the monofilament to bend, and if the patient is unable to feel this pressure in one or more of the recommended foot locations, it can indicate the cessation of large-fiber nerve function and frequently correlates closely with an ensuing ulceration.1Clinicians should first demonstrate the technique and sensation to the patient on an alternate location, typically the arm, to ensure that the patient understands what the sensation will feel like. During testing, the patient should close have closed eyes while the clinician applies pressure to the metatarsal heads of the 1st, 3rd, and 5th digits, and then to the plantar surface of the distal hallux. Bilateral feet should be tested and the results thoroughly recorded to ensure trending evaluations are accurate. Areas of callused skin should be avoided because the thicker skin can sense less and skew results.

128-Hz Tuning Fork

Like its counterpart, the 10-g monofilament, this is an economical and uncomplicated test that assesses the vibratory sensation of the foot. Engaging the fork by striking it on the clinician’s hand and then placing the end on the tip of bilateral great toes, LOPS is detected when the patient ceases to feel vibration while the clinician still feels it. An alternate test is the pinprick where the clinician uses a disposable pin to push on the dermis layer on each hallux. If the patient cannot feel the sensation, the test is considered abnormal.

Vascular Assessment

The evaluation for peripheral vascular disease (PVD) is vitally important because patients with PVD are at an increased risk for foot ulceration.1The palpation of bilateral posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses should be completed, and if they are found to be absent, the patient should be referred for further evaluation for an ankle brachial pressure index (ABI) pressure testing. An ABI result greater than 0.9 is considered normal, less than 0.8 is accompanied with claudication, and less than 0.4 occurs with chronic vascular compromise and discomfort.

Conclusion and Follow-Up

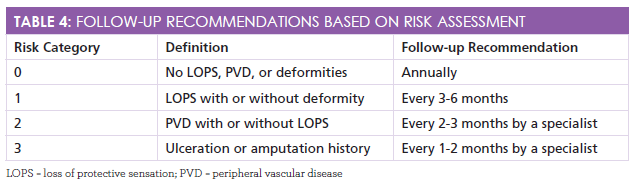

The prevention of diabetic foot ulceration requires assertive and continued teamwork by the provider and the patient.Table 4charts recommendations for follow-up to ensure continued reevaluations and reminding patients that wearing appropriate shoes, inspecting their feet daily, and being active participants in their health care can reduce the incidence of ulcerations.

Meghan L. Potter, RN, MSN, FNP-BC, is a 2005 cum laude graduate of Hampton University with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing. She worked in a busy emergency department before graduating from the University of Virginia with a Master of Science in Nursing with a concentration as a family nurse practitioner. Since graduation, she has been working full time as a nurse practitioner in the emergency department of a level 2 trauma center.

Reference

- Boulton AJM, Armstrong DG, Albert SF, et al; American Diabetes Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: a report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1679-1685. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9021.