Immunization Awareness: Are Your Young Patients Ready for the School Year?

The midst of summer break is the time to not only shop for new clothes, backpacks, and school supplies, but also for parents to ensure that their children’s immunizations are up to date.

In the midst of summer break, parents begin preparing their children for the school year ahead. Not only is it time to shop for new clothes, backpacks, and school supplies, but it is also time for parents to ensure that their children’s immunizations are up to date.

All states require children to be vaccinated against certain diseases as a condition for school attendance.1Because immunization requirements vary from state to state, however, it is important for pharmacy practitioners to be familiar with the recommended immunization schedules from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a division of the CDC, as well as with the requirements in the state in which they practice.

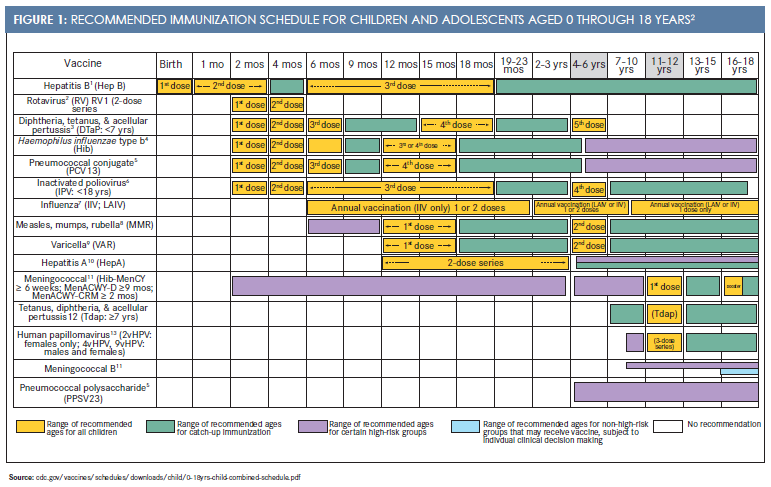

The ACIP regularly reviews, amends, and updates its immunizations schedules, so it is essential that clinicians refer to the most up-to-date schedules. The ACIP updated the immunization schedule in early 2016, andFigure 12shows the child/adolescent schedule.

Healthy People 2020 Objectives

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion currently targets 17 vaccine-preventable diseases across the life span. Despite recent progress, approximately 42,000 adults and 300 children in the United States die each year from vaccine-preventable diseases.3

One of the objectives of the Healthy People 2020 initiative is to increase immunization rates and reduce preventable infectious diseases. More specifically, the goal is to maintain vaccination coverage levels for children in kindergarten and increase routine vaccination coverage in adolescents.3

Vaccines are among the most cost-effective clinical preventive services. For each birth cohort vaccinated with the routine immunization schedule, society saves 33,000 lives, prevents 14 million cases of disease, and reduces direct and indirect health care costs by $9.9 billion and $33.4 billion, respectively.3The efficacy of the flu vaccine varies from year to year, as it was as high as 60% for the 2010—2011 flu season but was only 23% during the 2014–2015 flu season.4Other childhood vaccines produce immunity 90% to 100% of the time.5The reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States has already been described as one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 21st century.6

Immunization Requirements and Exemptions

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have laws that establish vaccination requirements for public schools and day care centers. In 47 states, the vaccine laws for private schools mirror those for public schools.1Vaccine requirements for postsecondary institutions are based on the individual institutions and may result in additional necessary immunizations. Being familiar with the different laws and requirements will prepare advanced practice clinicians to provide the best care for their patients.

State law establishes not only exemptions for school vaccination requirements, but also requirements regarding the exemption application process and the implications of an exemption in the event of an outbreak. According to data compiled by the CDC and the Public Health Law Program, Georgia and Arkansas have the most recognized exemptions to state law, with 6 different exemptions. Oklahoma and Illinois have the fewest, with no recognized exemptions to their state immunization laws.1To ensure that clinicians have the most current individual state requirements and exemptions for vaccines, a link to each state’s immunization website can be accessed at immunize.org/stateinfo.

Results from a recent study showed that patients were intentionally unvaccinated for nonmedical reasons such as religious or philosophical objections to vaccines in approximately 42% of recent measles cases in the United States. The results also showed that in 8 of the largest pertussis outbreaks for which there were detailed data, 59% to 93% of patients were intentionally unvaccinated for nonmedical reasons. Of significance, unvaccinated individuals were up to 20 times more likely to acquirethe infectionthan those who were vaccinated.7

Immunization Contraindications and Precautions

Although very few absolute medical contraindications to vaccines exist, a severe reaction or true anaphylaxis to a vaccine or its components is an absolute contraindication. Live vaccines should not be administered to pregnant patients or to those known to be severely immunodeficient.8

Precautions most commonly include moderate to severe illness at the time when the vaccine is to be administered. In any health care setting, including retail clinics, a sick visit may be the only opportunity to administer a vaccine to a patient in need of immunization. This makes it even more important to evaluate the severity of an illness carefully and to weigh the risk and benefits of administering the vaccine at the time of the visit or delaying in hopes that the patient will return for the vaccine at a later date.8

Common Immunizations in Retail Clinics

Because most retail clinics provide services to patients aged 12 to 18 months and older, the following recommendations are based on the 2016 ACIP vaccination schedule, not including vaccines scheduled prior to age 12 months.2

The influenza vaccine should be given annually to children aged 6 months and older, and 4 vaccines are given at age 4 to 6 years:

- The fifth and final dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (Dtap)

- The fourth and final dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV)

- The second and final dose of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR)

- The second and final dose of varicella (VAR)

Three additional infectious diseases are vaccinated against at age 11 to 12 years:

- One dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) is administered.

- Although the meningococcal vaccine is not required in all states, the ACIP recommends a dose at age 11 to 12 years. If the child does not receive his or her first dose until age 16 years or later, then a single dose is adequate. If the first dose is given prior to age 16 years, then a booster is given at age 16 to 18 years.

- As with the meningococcal vaccine, the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is not required by most states. The ACIP recommends that a 3-dose series be given to both male and female adolescents over a 6-month period, starting at age 11 or 12 years. A recent study found that just 10 years of vaccinating against HPV has cut infections from this cancer-causing virus by 64% among teen girls. Although these findings are encouraging, only 42% of girls and 22% of boys between the ages of 13 and 17 have received the recommended 3 doses of the vaccine.9

Additional Considerations for High-Risk Children

While the vast majority of children will already be immunized with most vaccines by 18 months of age, individuals who are considered high risk or are located in high-risk areas will require additional immunizations or boosters. The clinician should base his or her immunization advice on the following questions:

- Does the child live in a high-risk area for hepatitis A?

- Will the child be in a college dorm in the fall, so meningococcal infection is of greater concern?

- Does the child have a chronic illness such as asthma? If so, he or she will need an additional dose of PCV13 (pneumococcal conjugate vaccine) or a dose of PPSV23 (pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine).2

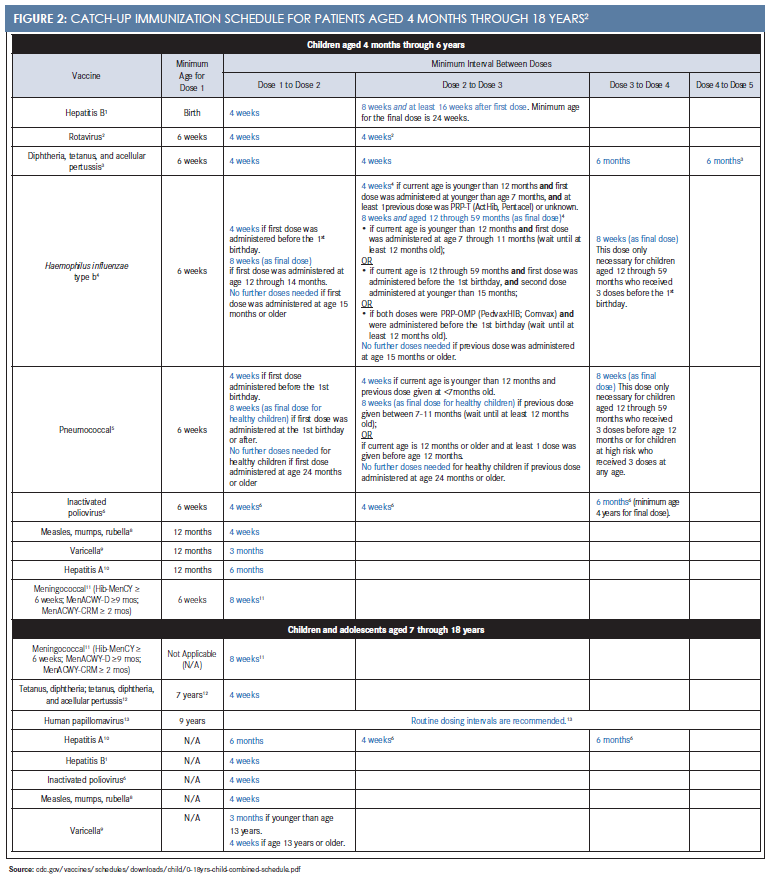

- Is the child behind on immunizations and in need of the catch-up vaccines such as hepatitis B? Practitioners should be familiar with the catch-up vaccination schedules recommended by the ACIP (Figure 22).

- Is the individual pregnant or might become pregnant? Influenza should be administered annually and, no matter when the last Tdap was administered,2a booster dose should be administered during the pregnancy. Live vaccines, however, including varicella and MMR, must be delayed until after delivery of the infant. Other vaccines should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to determine if the vaccine is necessary during pregnancy or can be delayed until after delivery.10

School admission is not the only reason to vaccinate children. When planning a trip abroad, it is important to know when and where the child will be traveling. Many countries either recommend or require additional vaccinations prior to travel. Some travel vaccines are a series of immunizations that require additional time to ensure the complete series is administered prior to travel, such as rabies, which requires a series of 3 vaccines over a 21- to 28-day period for full immunity.11The CDC website provides important information on the recommended vaccines for many countries and will assist the clinician in ensuring that patients are prepared for upcoming travel.12

Tuberculosis Screening

While not routinely screened for tuberculosis (TB), some school-age children are considered at high risk for this infection. When a child is brought to a retail clinic to receive other vaccinations, this is an ideal time for the clinician to inquire about his or her TB status.

Individuals who are considered at high risk for TB include13:

- People who have spent time with someone who has TB disease

- People with HIV infection or another medical problem that weakens the immune system

- People who have symptoms of TB (fever, night sweats, cough, and weight loss)

- People from a country where TB is common (most countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia)

- People who live or work somewhere in the United States where TB is more common (eg, homeless shelters, prison or jails, or some nursing homes)

- People who use illegal drugs

Administration of vaccines usually does not affect tuberculin skin test (TST) results when administered at the same time. If the TST cannot be administered on the same day as an MMR vaccine, the TST should be delayed for at least 4 weeks.8

Immunization Timing

Some parents may be concerned about administering several vaccines at one time and think this will compromise the child’s immune system, making the child ill. In reality, receiving multiple vaccinations on the same day is not associated with adverse effects.14-16It should be noted that when one or more live vaccine are to be administered, they must be given on the same day. If this is not possible, there should be a period of 4 weeks between vaccinations.2

In a survey from the late 1990s, 87% of respondents deemed immunization an extremely important action that parents can take to keep their children well, yet a substantial minority held important misconceptions. For instance, 25% believed that their child’s immune system could become weakened as a result of receiving too many immunizations, and 23% believed that children get more immunizations than are good for them. Of significance, health care providers are cited as the most important source of information about immunizations.17

Clinicians should use the tools at their disposal. The CDC and Immunization Action Coalition have many resources available for health care providers as well as informative handouts for patients and parents. The better the clinician understands vaccines, the more prepared he or she will be to respond to parents’ questions and concerns.

Conclusion

Parent and patient education is often the key to increase immunization rates. Clinicians should become familiar with the ACIP recommended vaccine schedules and be prepared to address questions and fears some parents may have regarding the use of vaccines. Keep an open mind when responding to parents’ or caregivers’ questions about immunizations. Being prepared to discuss these concerns calmly and provide evidence-based information will ensure improved immunization rates in your practice. Timely immunization of children in the United States with today’s vaccines is essential to maintaining our nation’s public health.

Ginger Urbanhas more than 30 years’ experience in health care. She is currently the regional clinical director for The Little Clinic in Arizona. Dr. Urban’s background includes family practice, emergency medicine, urgent care, academia, and health care administration.

References

- Public Health Law Office for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support. State school immunization requirements and vaccine exemption laws. CDC website. cdc.gov/phlp/docs/school-vaccinations.pdf. Published March 27, 2015. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years. United States 2016. CDC website. cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/child/0-18yrs-child-combined-schedule.pdf Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Immunizations and infectious diseases. Healthypeople.gov website. healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases. Updated April 18, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2005-2015. CDC website. cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectiveness-studies.htm. Updated February 25, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2016

- Vaccines are effective. How well do vaccines work? Vaccine.gov website. vaccines.gov/basics/effectiveness/. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kolasa M. National, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19—35 months—United States, 2014.MMWRMorb Mortal Wkly Rep.2015;64(33):889-896.

- Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Association between vaccine refusal and vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. A review of measles and pertussis.JAMA.2016;315(11):1149-1158.

- Guide to contraindications and precautions to commonly used vaccines in adults. Immunization Action Coalition website. www.immunize.org/catg.d/p3072.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, et al. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States.Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151968. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2016/02/19/peds.2015-1968. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Vaccinations for pregnant women. Immunization Action Coalition website. immunize.org/catg.d/p4040.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Rabies vaccine: What you need to know. CDC website. cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/rabies.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Travelers’ Health: Vaccines. Medicine. Advice. CDC website. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel. Accessed April 17, 2016

- Tuberculosis (TB): Testing and diagnosis. CDC website. cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/default.htm. Accessed April 17, 2016

- Too Many Vaccines? Immunization Action Coalition website. immunize.org/talking-about-vaccines/multiple-injections.asp. Updated May 11, 2015. Accessed March 27, 2016.

- Too many vaccines? What you should know. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Vaccine Education Center website. http://vec.chop.edu/export/download/pdfs/articles/vaccine-education-center/too-many-vaccines.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Questions parents ask about vaccinations for babies. Immunization Action Coalition website. immunize.org/catg.d/p4025.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2016.

- Gellin BG, Maibach EW, Marcuse EK, for the National Network for Immunization Information Steering Committee. Do parents understand immunizations? A national telephone survey.Pediatrics. November 2000;106(5):1097-1102. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/106/5/1097. Accessed April 17, 2016.