Effective Treatment for Acute Otitis Externa

An estimated 2.4 million medical visits between 2003 and 2007 resulted in a diagnosis of acute otitis externa, and annual related health care costs totaled $500 million for nonhospitalized patients alone.

An estimated 2.4 million medical visits between 2003 and 2007 resulted in a diagnosis of acute otitis externa (AOE), and annual related health care costs totaled $500 million for nonhospitalized patients alone.1Each year, AOE affects 4 of every 1000 individuals and is most prevalent in the older pediatric and young adult populations.2Although it can occur across the lifespan, it is seen less frequently in middle-aged and senior adults.3

The diagnosis of AOE peaks in children aged 7 to 12 years, and there is no predominant gender or ethnic predilection.2It is estimated that 10% of the population has or will have AOE at some point during their lifetime.3Most AOE diagnoses are made during the hot and humid months, and the condition can occur frequently in patients who are active swimmers, hence the nickname “swimmer’s ear.”4AOE is more common in southern states than elsewhere in the country.5

Educating higher-risk patient populations on AOE treatment can be beneficial despite the fact that the condition is typically self-limiting and resolves quickly and almost always without complications.

Pathophysiology

Otitis is inflammation and/or an infectious process of the ear. Three types of otitis can occur, and their names are indicative of the area of the ear they affect. AOE involves the outer ear and the external portion of the auditory canal, acute otitis media involves the middle ear, and otitis interna affects the inner ear. The main focus of this article is AOE.

Despite the body’s ability to protect itself from harm, the anatomy of the external auditory canal can be a factor in AOE development. The external auditory canal is the “only skin-lined cul-de-sac in the human body”; the skin in the canal is very thin and can be traumatized easily. The auditory canal is also very warm and dark and can become moist easily, aiding in the growth of fungus and bacteria. Additionally, the natural curvature in the canal can occasionally make it difficult for foreign bodies, debris, and secretions to exit properly, which again can result in fungal and/or bacteria development and subsequent AOE.6

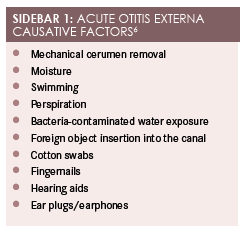

Cerumen is the ear’s natural defensive agent. It is composed of special substances that create a protective layer that inhibits fungal and bacterial growth. Because cerumen is also hydrophobic, it repels water from the auditory canal so that skin maceration does not occur. In addition to cerumen, the narrowing of the isthmus and the presence of hair follicles help to prevent foreign debris from entering the canal. AOE develops when a breakdown in the epithelial lining allows bacteria and/or fungus to flourish.Sidebar 16presents causative factors in the development of AOE.6

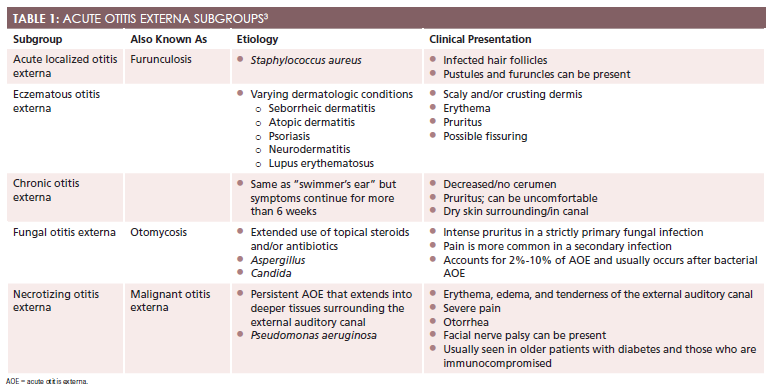

Besides the infectious bacterial process that causes “swimmer’s ear,” 5 other subgroups can be classified as AOE. These include furunculosis, chronic otitis externa, eczematous otitis externa, fungal otitis externa, and necrotizing otitis externa (Table 13).4

Diagnosis

Although a comprehensive history and physical examination are usually adequate for a diagnosis of AOE, additional testing and further evaluation for alternate diagnoses are warranted in some cases (Sidebar 22-6).2-4,6

SIDEBAR 2: RED FLAGS FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION2-6

- Fever >101°F

- Severe otalgia that is not diminished with oral analgesics and/or otic medications

- Lymphadenopathy

- Trismus

- Cranial nerve palsy

History of Present Illness

Onset.Symptom onset tends to occur rapidly (within 48 hours), and discomfort increases progressively in severity over that short time span.5The patient should be questioned about recent increases in water exposure, what he or she was doing when the discomfort was first noted, and whether the patient recently introduced anything into the ear, such as a cotton swab or hearing aid. Patients who have experienced a recent ear trauma (eg, object insertion into the canal) are at higher risk for AOE.2

Location.Determining the area of greatest discomfort will help decipher the type of otitis the patient is experiencing. Pain on palpation of the tragus and auricle manipulation or pulling are considered hallmark signs of AOE. It should be noted, however, that these signs may not be present or they may be very mild, especially in a patient who presents early in the course of infection. Although rare, patients may present with bilateral ear discomfort and have bilateral AOE. The infectious process may also involve additional soft tissue and bony structures, such as the mastoid bone, temporomandibular joint, or parotid gland; infections that invade these areas are severe and should be treated as such.2For those who present with otalgia but have neither ear canal edema nor acute otitis media, clinicians should consider diagnostic differentials that occur outside the ear (eg, temporomandibular joint disease).5

Duration.AOE can be present for a day or 2 before most individuals seek treatment. Depending on the severity of the discomfort, as rated by the individual patient, symptoms may be present for a shorter or longer duration. Patients whose symptoms last 6 weeks or longer should be evaluated for chronic otitis externa as well as other potential diagnoses.

Character.The most common symptoms related to AOE described by patients are otalgia and otorrhea. Complaints of otalgia can range from mild pruritus to severe discomfort. Patients have also described a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear. If a patient characterizes his or her discomfort as more of an itching sensation, then the individual is usually suffering from fungal or chronic otitis externa.2Immune-compromised patients or those with diabetes who describe deep and severe discomfort or pain that appears to be out of proportion for the diagnosis should be examined thoroughly because these populations are at increased risk for necrotizing AOE.2

Associated/Aggravating/Alleviating Factors.Most associated symptoms related to AOE are not indicative of a more serious infection, but some symptoms should alert the clinician to further evaluate the patient or refer the patient to an otolaryngologist (Sidebar 22-6). The patient should be questioned about difficulty hearing or complete loss of hearing on the affected side as well as whether he or she has experienced any tinnitus. If discharge is present, further descriptions of the discharge should be assessed. Discharge can change rapidly from odorless and clear to purulent and malodorous.2Patients who present with lesions that are vesicular in nature should be evaluated for Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus). In addition to the lesions and otalgia, individuals with Ramsay Hunt syndrome may experience facial paralysis, decreased lacrimation on the affected side, and loss of taste sensation. Although the condition is rare, systemic antivirals and steroids should be initiated promptly in these patients.5

Radiation.The patient should be asked whether discomfort radiates down the neck or into the jaw. Some serious differentials, including mastoiditis, should be considered in a patient who experiences radiating discomfort. Although mastoiditis occurs most frequently in patients with acute otitis media and it has become more rare since the introduction of antibiotics for the treatment of acute otitis media, clinicians should be sure to include this in their differential diagnosis.

Timing.It is important to discuss the timing of signs and symptoms with patients. According to the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, the onset of symptoms in AOE is typically 48 hours. The symptoms should have begun within the 3 weeks prior to the patient’s presentation for evaluation. Again, there has been a high correlation with warmer months and patients who have had increased exposure to water activities. Patients should be re-evaluated within 48 to 72 hours if their symptoms fail to respond to treatment.5

Severity.When consulting with patients about the severity of their illness, it is important to discuss their pain level in detail. In addition to asking patients to rate their discomfort on a scale from 1 to 10 and to compare their discomfort with another type of pain they have experienced (eg, childbirth, a stubbed toe, herniated disk), further investigation and questioning can help gauge how troublesome the symptoms have been. For example, has discomfort resulted in daily activity interference, missed work, or the inability to sleep? These questions will not only assist the provider, but they will also help to build a strong rapport with the patient.

Past Medical History

The medical history of any individual is always pertinent and should always be considered as it can help the clinician decipher the acute versus chronic nature of the presenting complaint. Several patient populations are at higher risk for developing complications or presenting with signs and symptoms similar to those of AOE, but their true diagnosis could be much worse. As noted, elderly, immunocompromised, or diabetic patients who present for evaluation of severe ear pain should be referred for further evaluation by an otolaryngologist to determine whether necrotizing otitis externa is present. These populations are also at risk for skull base osteomyelitis, so thorough discussion of the patients’ medical history is very important.

Physical Examination and Diagnostics

A thorough physical exam is not only important for the health of your patients, but it also most often leads to a firm diagnosis without the need for expensive laboratory and radiologic testing. With AOE, an otoscopic exam is of utmost importance. During this exam, the clinician should look around the external ear and surrounding structures for skin changes, including color, edema, masses, and otorrhea. The tympanic membrane and middle ear should be assessed. Depending on the severity of the AOE, it may be difficult to visualize the tympanic membrane due to discomfort and surrounding edema. Occasionally, children will have placed a foreign body into the ear canal, thus causing their symptoms. A battery placed into the canal is considered a medical emergency, and it should be removed promptly.2

Although AOE is a diagnosis based on the history and physical exam, some cases may require an additional workup involving laboratory and radiologic testing. Cultures from the ear canal typically are not necessary unless the infection is not responding to treatment. In these cases, cultures may help narrow the antibiotic choice to ensure that the offending bacterium is targeted. If obtaining blood work, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate is often highly elevated with necrotizing otitis externa.4

For individuals who are at risk for necrotizing otitis externa or mastoiditis, a computed tomography (CT) scan is the preferred radiologic study as it can better delineate bony erosion.2If CT is unavailable, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered. If the dominating concern is infection extension into the soft tissue, the MRI would be the better way to evaluate.

Treatment

The multiple treatment goals with regard to AOE include pain management, debris removal from the external ear canal, and topical medication administration.3An OTC pain medication and topical eardrops are usually sufficient for most patients with AOE, although in severe cases oral or intravenous antibiotics and narcotic pain medications may be required.2

If noticeable debris is present at the canal entrance, gentle cleaning can benefit the patient, as it increases the effectiveness of topical medications. If the tympanic membrane is intact and additional debris is present in the canal, a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and warm water may be instilled to help flush out the remains. If this is pursued, any leftover fluids should be removed to ensure that symptoms are not exacerbated.

Current medication recommendations for treatment of AOE are discussed inTable 22. One of the most frequently prescribed is a combination medication containing acetic acid and an antibacterial agent. The acetic acid alters the pH of the ear canal to make it more difficult for bacteria to grow, and the antibiotic diminishes bacterial growth.2Most of these suspensions are already mixed for easy prescribing ability and ease of use by the patient.

TABLE 2: OTITIS EXTERNA MEDICATIONS2

Generic Drug Name

Brand Name

Drug Class

Dosage

Hydrocortisone/neomycin/

polymyxin B

Cortisporin, Cortimycin

Corticosteroid/

aminoglycoside/antibacterial

4 drops in affected ear 3 times daily for 10 days

Ofloxacin otic

Ocuflox

Quinolone

Age 6 months to 13 years: 5 drops in affected ear daily for 7 days

Age 14 to adult: 10 drops in affected ear daily for 7 days

Ciprofloxacin

Cetraxal

Quinolone

Age >1 year: 5 drops in affected ear twice daily for 7 days

Dexamethasone/tobramycin

TobraDex

Aminoglycoside

Age >1 year: 1—2 drops in affected ear every 2 hours for 1 or 2 days, then taper dose gradually to discontinue use

Gentamicin

Garamycin, Gentak

Aminoglycoside

1—2 drops in affected ear 2 or 3 times daily

Ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic

Ciprodex

Quinolone

Age >6 months: 4 drops in affected ear for 7 days

Clotrimazole 1% otic

Lotrimin AF

Antifungal

4 drops in affected ear 4 times daily for 7 days

Some patients will require placement of an ear wick due to the amount of edema present; this will aid in the ability of the otic medications to get to where they are needed. An ear wick will usually fall out after the swelling has decreased, but if it has not migrated out on its own after 2 days it should be removed manually. Patients diagnosed with necrotizing otitis externa typically require extensive intravenous therapy that can last from 1 to 3 months.

It is important for clinicians to note that prevention of AOE is possible, especially in higher-risk patient populations. Avoidance of contributing factors by keeping the ear canal dry and avoiding insertion of foreign objects into the canal is usually the easiest and most effective method of prevention.

Meghan Potteris a cum laude graduate of Hampton University with a bachelor of science in nursing. She worked in a busy emergency department before graduating from the University of Virginia, where she obtained her master of science degree in nursing with a concentration as a family nurse practitioner. Since graduation, she has been working full-time as a nurse practitioner in the emergency department of a level 2 trauma center.

References

- CDC. Estimated burden of acute otitis externa—United States: 2003—2007.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(19):605-609. cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6019.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- Waitzman AA. Otitis externa. Medscape website. emedicine.medscape.com/article/994550-overview. Updated August 13, 2015. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- Goguen LA. External otitis: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate website. uptodate.com/contents/external-otitis-pathogenesis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?source=search_result&search=external+otitis&selectedTitle=2~79. Updated September 19, 2014. Accessed February 10, 2016.

- Ferri FF. Otitis externa. In: Ferri FF, ed.Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2013: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2012.

- Rosenfeld RM. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(1):S1-S24.

- Sander R. Otitis externa: A practical guide to treatment and prevention.Am Acad Fam Physicians. 2001;63(5):927-937.

- Goguen LA. External otitis: Treatment. UpToDate website. uptodate.com/contents/external-otitis-treatment?source=search_result&search=external+otitis&selectedTitle=1~79. Updated September 4, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2016.