GERD in the Retail Clinic: When to Treat and When to Refer

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is the most common gastrointestinal disorder for which patients seek treatment.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder for which patients seek treatment. Each year, GERD affects up to 60% of Americans, of whom an estimated 20% to 30% are symptomatic weekly.1However, these figures may actually be higher because patients can purchase OTC medications for GERD symptoms.2

The physiologic process of gastroesophageal reflux is normal, thereby making a clear definition of GERD difficult. Physiologic gastroesophageal reflux is problematic when it begins causing discomfort and/or decreases the patient’s quality of life, at which point it becomes pathologic reflux. In 2006, a panel of 44 experts from 18 countries developed what is now known as the Montreal definition of GERD: “a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.”3

GERD Pathophysiology

The GI system is a muscular tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. It comprises 4 major regions: the mouth and esophagus, the stomach, the small intestine, and the large intestine and anus. These organs each have separate yet important roles in the digestive process. The esophagus is responsible for transporting food from the pharynx to the stomach, but it plays no role in digestion or absorption. Acid secretion, production of intrinsic factor, and the initial breakdown of food take place in the stomach, and then the small intestine continues food digestion and absorbs nutrients and other materials into the bloodstream. Finally, the large intestine reabsorbs water and passes any undigested food through to create stool, which exits through the anus.

GERD is the most common disease process of the esophagus and is seen when dysfunction occurs with the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), or the stomach. When there is decreased esophageal motility, acidic contents remain immobilized, causing irritation to the esophageal tissue. Similarly, if the LES is dysfunctional, a backup of acidic gastric contents to the esophagus occurs.

There are 3 ways in which the LES can fail to function properly: intermittent relaxation, permanent relaxation, or overpowering abdominal pressure that surmounts the LES. The stomach acts as a reservoir until gastric contents are moved through the small and large intestines. In the presence of delayed gastric emptying, increased pressure and volume force the gastric contents back through the LES and into the esophagus, consequently irritating esophageal tissue and causing GERD symptoms. From a treatment perspective, it is important to know where the area of dysfunction originates in order to select the best therapy for the patient.

GERD Signs and Symptoms

A number of common signs and symptoms are associated with GERD, including heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia. In the postprandial phase of digestion, heartburn is characteristically described as a retrosternal burning sensation that may be present for hours after eating. Regurgitation is the unforced reappearance of gastric and/or esophageal contents into the pharynx.4 The regurgitative process typically involves acidic gastric juices that may mix with a diminutive quantity of undigested food.2Dysphagia is also common in patients with prolonged symptomatology of GERD and is typically considered an advanced symptom. In the presence of dysphagia, patients should also be evaluated for reflux esophagitis and clinicians should be concerned about a potential stricture.4

Atypical symptoms, including chest pain, water brash, cough/wheezing, laryngitis, dental erosions, nausea, and abdominal pain, can also be present in patients with GERD and often mimic more serious disease processes. Patients who present with chest pain should be evaluated thoroughly for angina before being diagnosed with GERD. Hypersalivation, or water brash, and odynophagia are infrequent complaints, but when they are present in an asymptomatic patient, they should alert the clinician to a potential ulcer.4

GERD Treatment Options

Like most disease processes, the treatment of GERD involves a multitude of steps that start with the least invasive approach and escalate if the patient remains symptomatic. The initial goal of therapy is to control symptoms so that the esophageal mucosa can begin to heal. Once healing has begun, prevention of any further symptoms is imperative, as continuous injury and damage to the mucosa increase a patient’s risk for more serious complications such as Barrett’s esophagus and cancer. Treatment may include lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic interventions, and surgery.

Lifestyle Modifications

Some of the most causative agents associated with GERD are related to diet. Many types of food and drink and lifestyle habits can exacerbate GERD symptoms. Beverages that may cause symptoms include coffee, citrus juices, and carbonated drinks; culpable foods include fried and spicy items, chocolate, peppermint, onions, and tomato- based products.2Current guidelines advise against complete elimination of all potentially causative agents, instead suggesting elimination only if the patient notes a correlation between symptoms and specific foods.5Tobacco and alcohol, both of which decrease LES pressure, should be avoided.

Although there are conflicting studies and a lack of concrete evidence linking obesity to GERD, weight loss in the obese patient is highly recommended.1-3Additional recommendations include eating small, frequent meals instead of large meals and completing the final daily meal at least 3 hours before lying down for bed. For patients whose symptoms continue when lying down, elevating the head off the bed by 8 inches may also help.2Some alternative therapies that have not been consistently linked with symptom reduction, but are practical and simple, include avoiding tight-fitting clothing and performing abdominal breathing exercises.5

Pharmacologic Interventions

For patients who have little to no change in symptoms after lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic interventions may be beneficial, as they can decrease and/or eliminate symptoms and allow for esophageal mucosa healing. Three classes of medications are used to treat GERD symptoms: antacids, H2receptor antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Antacids typically comprise 1 to 3 different compounds that together help neutralize elevated gastric acid levels and thus reduce symptoms. The function of antacids in GERD treatment is limited, however, because they only decrease symptoms and play no role in helping to prevent them. Antacids can begin to improve symptoms 5 minutes after ingestion, but their effectiveness is short-lived (30-60 minutes), so they are only recommended for short-term (≤1 week) or intermittent therapy.5

H2receptor antagonists are beneficial in patients whose symptoms persist despite intermittent antacid therapy, but these agents are only partially effective in patients with erosive esophagitis. The drug class inhibits H2receptors on the gastric parietal cell, consequently decreasing acid secretion. Peak concentrations are reached approximately 2.5 hours after consumption and can last for 4 to 10 hours. Efficacy among available H2receptor antagonists is comparable and dosing is twice daily. For patients with a history of cognitive or renal impairment, H2receptor antagonists should be avoided because they can increase baseline confusion or worsen renal function. An acute and rapid decreased symptom response or tachyphylaxis can occur within 2 to 6 weeks. Long-term use of H2receptor antagonists should be avoided.5

PPIs should be initiated in patients for numerous reasons, including failure of symptomatic improvement on H2receptor antagonists, acute symptoms that decrease quality of life, and/or symptoms that occur 2 or more times a week. Patients with confirmed erosive esophagitis should also be started on PPI therapy. PPIs irreversibly bind to the proton pump of the gastric parietal cell and inhibit the majority of the gastric acid produced daily.5They can take up to 5 days to become effective, however, so they should not be used for acute treatment.

Effectiveness is equal among all PPIs, and dosing can be initiated in one of 2 ways. For severe symptoms, the patient should be started on a higher daily dose and then tapered to a lower dose after 4 to 8 weeks. If symptoms are resolving after 12 weeks, the patient should be taken off PPIs. If symptoms recur, the patient should be referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation and more invasive testing. The lowest effective dose for the shortest duration for symptom control should be considered and risks versus benefits should be thoroughly evaluated in all patients. This is because long-term PPI use has been linked toClostridium difficileinfection, hypomagnesemia, anemia, decreased bone mineral density, and gastric cancer. In addition to potentially significant adverse reactions, PPIs also have possible drug—drug interactions with digoxin, warfarin, phenytoin, and clopidogrel. For more information on drug–drug interactions with GERD therapies, read “PPIs and Antacids: How to Avoid Interactions” in this issue.

Surgical Treatments

When lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic treatments are ineffective at relieving symptoms, surgical intervention may be appropriate. Indications for surgical intervention of GERD include refractory symptoms despite PPI therapy, poor medication compliance, presence of Barrett’s esophagus, osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, and flawed cardiac conduction.2For these patients, a Nissen fundoplication is indicated. This procedure involves wrapping the upper portion of the stomach around the lower portion of the esophagus and stitching it in place. The pressure created from this procedure strengthens the LES and helps prevent and/or treat a hiatal hernia. A 10-year survey of patients following fundoplication surgery demonstrated that about 90% remained symptom-free and very few were still on PPI therapy.6

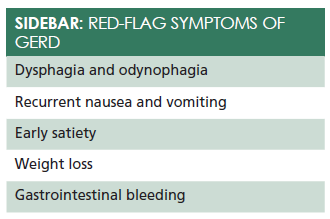

With their ability to self-medicate with OTC options, patients may not immediately disclose GERD symptoms to their clinician. Some red-flag symptoms that could indicate an alternate disease process or worsening GERD should raise concern among retail clinicians and spur referral for further evaluation by a gastroenterologist (Sidebar). Although dysphagia and odynophagia could be related to a long-standing history of GERD, patients with these symptoms should be evaluated for Barrett’s esophagus. Males older than 45 years who have a prolonged history of GERD, patients who abuse tobacco and have had weekly symptoms for longer than 1 year, obese patients with weekly symptoms over a 1-year period, those with a history of erosive gastritis, and the elderly should also be referred for further evaluation, even if no red flag symptoms are present. In addition, those who have initiated PPI therapy and have refractory symptoms should be referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation and diagnostic testing.

Conclusion

Millions of patients worldwide experience the symptoms of GERD. Most symptoms can be significantly decreased or controlled with a variety of treatment options that provide relief while helping the body heal, but some patients require further evaluation and treatment by a GI specialist. Initiation of lifestyle modifications, in addition to pharmacologic therapies, can help most patients live a symptom-free life. Patients who present with GERD red flags and refractory symptoms should be referred for further evaluation and management.

Meghan Potter is a cum laude graduate of Hampton University with a bachelor of science in nursing. She worked in a busy emergency department before graduating from the University of Virginia, where she obtained her master of science degree in nursing with a concentration as a family nurse practitioner. Since graduation, she has been working as a full-time nurse practitioner in the emergency department of a level 2 trauma center.

References

- Zhao Y, Encinosa W. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) hospitalizations in 1998 and 2005. HCUP Statistical Brief #44. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/ sb44.jsp. Published January 2008. Accessed January 5, 2016.

- Patti MG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Medscape website. emedicine.medscape.com/article/ 176595-overview. Updated January 3, 2016. Accessed January 5, 2016.

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus.Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900-1920;quiz 1943.

- Kahrilas PJ. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux in adults. UptoDate website. uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestationsand- diagnosis-of-gastroesophageal-reflux-in-adults. Published March 11, 2015. Accessed December 2, 2015.

- Kahrilas PJ. Medical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults. UpToDate website. uptodate.com/contents/medical-management-of-gastroesophageal- reflux-disease-in-adults. Published April 27, 2015. Accessed December 2, 2015.

- 6. Dallemagne B, Weerts J, Markiewicz S, et al. Clinical results of laparoscopic fundoplication at ten years after surgery.Surg Endosc. 2006;20(1):159—165.