Best Approaches to Acute Gastroenteritis

Each year, there are approximately 179 to 350 million cases of gastroenteritis in the United States, resulting in approximately 600,000 hospitalizations.

Each year, there are approximately 179 to 350 million cases of gastroenteritis in the United States, resulting in approximately 600,000 hospitalizations.1,2Alarmingly, the number of gastroenteritis-associated deaths in the United States more than doubled from approximately 7000 in 1999 to beyond 17,000 in 2007. Worldwide, it is currently one of the leading causes of death.3Patients aged older than 65 make up the majority of these deaths in the United States (83%), two-thirds of which result fromClostridium difficileinfection.2

Although the vast majority of gastroenteritis cases in the United States are self-limiting and not life-threatening, the condition remains the cause of considerable morbidity and economic burden.4Norovirus alone is responsible for $2 billion in health care costs and lost productivity annually,5and foodborne illnesses impose an overall economic burden exceeding $15.5 billion annually.4About 90% of foodborne gastroenteritis cases can be attributed to just 5 pathogens.

Learning how to prevent, identify, and treat acute gastroenteritis is imperative for health care providers and public health.

Epidemiology

Acute gastroenteritis is inflammation and/or irritation of the digestive tract that can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or abdominal pain that lasts less than 14 days. When symptoms last 14 to 30 days, the condition is considered persistent gastroenteritis. When symptoms last longer than 30 days, it is considered chronic.2

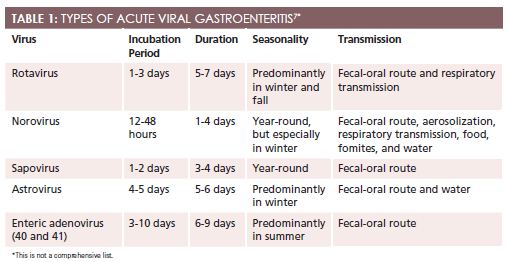

Various pathogens and noninfectious agents cause gastroenteritis, and it is one of the most common infectious disease syndromes.2In the United States, viral gastroenteritis accounts for about 50% to 70% of acute gastroenteritis cases, with norovirus being the leading cause.2,6Other causes of acute viral gastroenteritis are presented inTable 17. Since the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine, the incidences of rotavirus gastroenteritis and related hospitalizations have been greatly reduced.8On the other hand, norovirus is common and highly contagious.

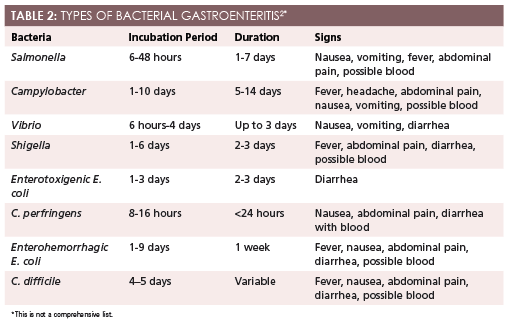

After viral gastroenteritis, another 10% to 15% of acute cases have a parasitic cause, while bacterial gastroenteritis accounts for about 15% to 20% of cases. Types of bacterial gastroenteritis are presented inTable 22.

Infectious diarrhea can also be classified into 2 categories: inflammatory or noninflammatory. Noninflammatory diarrhea is more common, and although the cause is usually viral, it can be bacterial or parasitic in origin, as well. Noninflammatory diarrhea, which is typically less severe than inflammatory diarrhea, causes large, watery stool with cramping but no blood; fecal leukocytes are absent. Common causes of noninflammatory diarrhea are enterotoxigenicEscherichia coli,Clostridium perfringens,Bacillus cereus,Staphylococcus aureus, rotavirus, norovirus,Giardia,Cryptosporidium, andVibrio cholerae. Inflammatory diarrhea is more severe and caused by toxin-producing bacteria. It disrupts the mucosa, causing bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever, and fecal leukocytes are present. Common causes of inflammatory diarrhea areSalmonella,Shigella,Campylobacter, Shiga toxin-producingE. coli, enteroinvasiveE. coli,C. difficile,Entamoeba histolytica, andYersinia.9SeeTable 32for other epidemiologic considerations in acute gastroenteritis.2

TABLE 3: OTHER EPIDEMIOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS2

Travel (in general)

E. coliis the most common cause of traveler’s diarrhea. Symptoms usually begin within a few days of arriving and last 5 days to 2 weeks.

Travel to Asia, Africa, and South America

12% of diarrheal illness may be caused by rotavirus.

Asia and Central America

Vibriospecies is more common.

Travel to developing countries

Bacterial and parasitic infections are more common.Giardia lamblia, Aeromonas, andCryptosporidiumare often found in contaminated water.

Recent antibiotic use

These patients carry a higher risk forC. difficileinfection.

Daycare

Children and their families are at higher risk for rotavirus infection.

Homosexual men

These men are at higher risk for infection withShigella,Campylobacter jejuni,Salmonella, and protozoa-likeEntamoeba. HIV-infected patients with a CD4 count <200 are at increased risk for infection byMycobacterium aviumcomplex, microsporidia, cytomegalovirus, andCystoisospora belli.

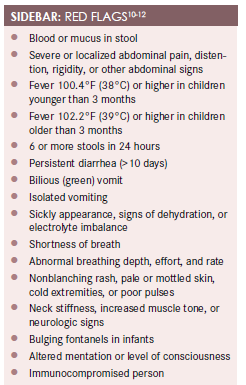

In the United States, a large portion of gastroenteritis cases are caused by self-limiting viruses and generally do not require labs or stool culture, unless warranted by certain red flags (Sidebar10-12). A thorough history and physical exam are usually sufficient for diagnosis.

History of Present Illness

- Onset:Paying close attention to the onset of symptoms can be particularly helpful in making a specific diagnosis, given the various incubation periods among pathogens. Did symptoms begin shortly after eating? Did they occur while traveling to a different country? Did they begin while babysitting? Have the symptoms been ongoing for weeks or years?

- Location:Are the symptoms generalized nausea and diarrhea or is the patient able to point to a specific area of pain? The abdominal exam is an important part of ruling out red flags. When a patient complains of abdominal pain, the various causes of an acute abdomen or referred pain should be considered. Upper abdominal pain could be acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis, or a perforated ulcer. Mid-abdominal pain could be a sign of intestinal obstruction or mesenteric ischemia. Lower abdominal pain could be appendicitis or sigmoid diverticulitis, or it could have a gynecologic or urologic cause. Patients with gastroenteritis should not have rebound tenderness, guarding, distention, bulges, pinpoint pain, or a board-like abdomen.13

- Duration:Acute infectious gastroenteritis lasts fewer than 14 days, and most viral cases typically last fewer than 4 days. Symptoms occurring longer than this warrant further investigation.

- Character:The character of diarrhea and vomit, as well as pain, is especially important when differentiating between viral and bacterial causes of gastroenteritis. The clinician should ask questions about frequency and quality of vomiting and diarrhea. What color is the stool and vomit? Is the stool watery, bloody, explosive, painful, cramping, pale, clay-colored, or dark, or does it have mucus? Is the vomit green, bloody, black, or like coffee grounds? The history should include questions that determine whether the patient is bleeding, if there is significant inflammation, and which part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract appears to be affected.

- Associated/aggravating/alleviating factors:Is there a constellation of symptoms or is the vomiting, diarrhea, and/or abdominal pain isolated? If symptoms are isolated, differentials should be reviewed carefully. Do certain foods lead to diarrhea? If the patient frequently experiences gas or diarrhea after eating certain foods, then noninfectious causes such as food intolerances or irritable bowel syndrome should be considered.

- Pain radiation:Does the pain radiate to the back, to the right lower quadrant, or to the left side? Serious conditions can masquerade as GI symptoms. Sometimes, myocardial infarction can appear as dyspepsia and epigastric pain. In children, abdominal pain may be the only presenting feature in pneumonia.

- Timing:Asking about the timing of symptoms is crucial in determining whether the condition is chronic, acute, infectious, or noninfectious. Uncovering the exact offending agent in acute gastroenteritis is difficult without a culture and usually unnecessary, as treatment is mostly supportive. However, a good history and physical examination can lead the clinician in the right direction.

- Severity:Acute viral gastroenteritis is usually less severe than bacterial gastroenteritis. Hydration should be considered when investigating the severity of symptoms, as severe diarrhea or vomiting could quickly lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances that can be fatal in vulnerable populations. The very young and the very old, immunocompromised individuals, and malnourished patients are most at risk. Mild to moderate dehydration can cause dry mouth, fatigue, sleepiness, thirst, decreased urine output, dry skin, constipation, and dizziness. Severe dehydration—which is an emergency—can cause extreme thirst, extreme sleepiness, sunken fontanels, and fussiness in infants; irritability/confusion in adults; and dry mucous membranes, little urine to anuria, sunken eyes, tenting, hypotension, tachycardia, rapid breathing, fever, and delirium in individuals of any age. Severe volume depletion can cause bradycardia; deep, erratic respirations; and hypothermia.2

Medications

Many medications can cause gastroenteritis, so a careful review of all medications and supplements that a patient has been taking is important. Examples of medications that frequently cause gastroenteritis are chemotherapeutics, antibiotics, laxatives, sorbitol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cardiac antidysrhythmics, and colchicine.2

Allergies

Some patients experience GI intolerances with many medications, which may be listed in their medical record. Asking about allergies can lead clinicians to consider possible noninfectious causes of gastroenteritis and aid them in selecting an appropriate antibiotic if one is warranted.

Past Medical History

Patients who are immunocompromised or very young or very old are at higher risk for complications and death from severe dehydration. Knowing a patient’s health history is important in determining whether more aggressive action or investigation is needed and how vigilant the follow-up should be. The medical history can also tell the clinician if this is likely a chronic problem, an acute problem, or an infectious or noninfectious problem.

Social History

Because many pathogens have stereotypic scenarios, the patient’s social history provides key clues into the type of pathogen involved. The patient should be asked about recent travel, contact with children or daycare centers, occupation, recent meals, onset of symptoms related to meals, and whether anyone they know has experienced these symptoms.

Other Diagnostics

Vital signs should be reviewed to determine severity of illness and stability. What does the patient look like? Common causes of gastroenteritis, such as norovirus, typically do not cause patients to look toxic. Therefore, a toxic- looking patient warrants investigation and prompt treatment or referral.

The heart and lungs should be auscultated to check for abnormal breathing, irregular heartbeat, tachycardia, bradycardia, and murmurs. A detailed abdominal exam should include close attention to bowel sounds, abdominal distention, masses/bulges, pain, tenderness, guarding, radiating pain, or rebound tenderness.2The skin and oral mucosa should be examined for signs of dehydration, as well as skin color and texture. Tenting, cracked lips, peeling lips, scaly skin, lack of tears, sunken fontanels, sluggish capillary refill, and sunken eyes are signs of dehydration.

Stool cultures are generally reserved for patients with a suspected nosocomial infection and those who are immunosuppressed, have blood or mucus in the stool, show signs of severe dehydration or inflammatory disease, or have symptoms lasting more than 3 to 7 days.9

Treatment

In acute viral gastroenteritis, the focus is on treating symptoms and preventing dehydration. Resting; eating a soft, bland diet; and drinking fluids with a proper balance of electrolytes can help patients recover. Children and adults can drink water, Pedialyte, and oral rehydration solutions.

Bacterial and parasitic infections are treated with appropriate medication, rest, hydration, and a gastroenteritis diet. Treating bacterial gastroenteritis with empiric antibiotics is controversial. Overuse of antibiotics can lead to resistance and may cause secondary infections such as aC. difficileand yeast infections, prolong the carrier state, induce Shiga toxins, and increase costs. Antibiotics have been shown to be effective for shigellosis, campylobacteriosis,C. difficileinfection, traveler’s diarrhea, and protozoal infections. If the patient presents with symptoms suggestive of Shiga toxin—producingE. coli, then antibiotics should not be used because of the risk for hemoly tic-uremic syndrome.9

Gastroenteritis Diet

Diet is a large portion of acute gastroenteritis treatment. The goal is to aid in patient comfort while maintaining hydration and nutrition. Foods to avoid with all age groups include caffeine; fatty foods; spicy foods; sharp foods such as seeds, nuts, and chips; sugary foods and desserts; carbonated drinks; fruit juices; and alcohol.14Recommended foods for older children and adults include soft, bland, easy-to-digest foods such as bananas, brown rice, broths, potatoes, plain natural applesauce, oral rehydration solutions, and whole grain bread. Infants should be given breast milk or infant formula.14The key to nutrition and hydration is frequent sips of liquids and small volumes of food at a time. Too much liquid or food at once can cause discomfort and worsen symptoms.

Prevention

The best way to prevent the spread of infection is proper hand hygiene. Patients should be educated on when and how to wash their hands with soap and water, as well as when alcohol-based rubs are appropriate. Other actions that patients can take to reduce their risk for contracting and spreading gastroenteritis include:

- Be up-to-date on immunizations, including flu and rotavirus vaccinations.

- Avoid eating communal foods and at buffets.

- Handle food properly.15

- Avoid undercooked meats.

- Drink bottled water, and avoid raw and peeled fruit and vegetables when traveling.

- Avoid close contact and sharing personal items with others.

- Disinfect surfaces at home with ½ cup of bleach to 1 gallon of water. Apply the solution to surfaces and let it dry for 5 minutes. Rinse thoroughly and allow it to air-dry.16

- Frequently wash bedding, pillows, and blankets.

Sara Marlow is a licensed and board-certified family nurse practitioner, public health nurse, and adjunct assistant professor of health policy. She was the spring 2015 Health Policy Fellow in Washington, DC, at the American Association of Nurse Practitioners’ government affairs office and is the current co-chair of the Health Policy and Practice Committee of the California Association for Nurse Practitioners.

References

- Hall AJ, Rosenthal M, Gregoricus N, et al. Incidence of Acute Gastroenteritis and Role of Norovirus, Georgia, USA, 2004-2005.Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(8):1080 - 6059. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101533.

- Graves N. Acute Gastroenteritis.Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2013;40(3):727-741. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.05.006.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths from gastroenteritis double. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2012/p0314_gastroenteritis.html. Published March 14, 2012. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Economic Burden of Major Foodborne Illnesses Acquired in the United States. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1837791/eib140.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Burden of Norovirus Illness and Outbreaks. http://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/php/illness-outbreaks.html. Published July 8 2014. Accessed December 18, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks of Acute Gastroenteritis Transmitted by Person-to-Person Contact — United States, 2009—2010. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6109.pdf. Published December 14, 2012. Accessed December 17, 2015.

- Barr W, Smith A. Acute Diarrhea in Adults.American Family Physician. 2014: 89(3): 180-9. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2014/0201/p180.html#afp20140201p180-b3. Accessed December 18, 2015.

- Matson, D . Epidemiologic and clinical features of common causes of acute viral gastroenteritis in children. In: Torchia M, ed.UpToDate,Waltham, Mass.:UpToDate:2015. http://www.uptodate.com.samuelmerritt.idm.oclc.org/contents/image?imageKey=PEDS%2F80471&topicKey=PEDS%2F5984&rank=4~150&source=see_link&search=gastroenteritis&utdPopup=true. Published

- Diskin A, Gutierrez-Alvarez L. Emergent Treatment of Gastroenteritis Clinical Presentation: History, Physical, Causes.Emedicinemedscapecom. 2015. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/775277-clinical. Accessed December 20, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pinkbook | Rotavirus | Epidemiology of Vaccine Preventable Diseases. Center for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rota.html. Published September 8 2015. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Burden of Norovirus Illness and Outbreaks. Center for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/php/illness-outbreaks.html. Published July 8 2014. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Clinical Practice Guidelines : Gastroenteritis. 2015. Available at: http://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Gastroenteritis/. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- Karnath B, Mileski W. Acute Abdominal Pain.Hospital Physician. 2015. Available at: http://www.turner-white.com/pdf/hp_nov02_pain.pdf. Published November 2002. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- Kerr S. Gastroenteritis Diet.Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. 2012. Available at: http://www.bidmc.org/YourHealth/Holistic-Health/Diet-Center.aspx?ChunkID=648850. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis in under 5s: diagnosis and management | guidance | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. 2009. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/chapter/guidance. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- Tablang M, Wu G, Grupka M. Viral Gastroenteritis Workup. 2015. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176515-clinical. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Basics for Handling Food Safely. 2015. Available at: http://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/get-answers/food-safety-fact-sheets/safe-food-handling/basics-for-handling-food-safely. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- Clorox. Making sure you dilute bleach | Clorox. 2013. Available at: https://www.clorox.com/dr-laundry/making-sure-you-dilute-bleach/. Accessed December 19, 2015.