Cholesterol Screening: What Retail Clinicians Should Know

Cholesterol is of great importance because of its impact on atherosclerosis.

Cholesterol is of great importance because of its impact on atherosclerosis.1,2Health care providers should understand atherogenesis as a deposition of lipids essentially causing chronic, inflammatory changes.2Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the United States, and atherogenesis and subsequent atherosclerosis are the cardiovascular processes that lead to most of these mortalities.1,2

Oxidative stress and inflammation are 2 leading factors thought to accelerate the progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).3Preventing the progression of these processes is fundamental to patient management. A hallmark in prevention is early identification of risk factors (eg, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, and high total cholesterol)4to guide treatment and ameliorate progression of the ASCVD process.

Lipoprotein Classes

The 2013 American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the management of cholesterol are more effective than the 2004 ACC/AHA guidelines at identifying increased risk for cardiovascular disease events.4To guide clinicians in applying these guidelines, an understanding of the 3 classes of lipoproteins is essential:

- Very-low-density lipoproteins comprise most of the triglycerides in the blood.

- Low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) comprise the majority of all cholesterol in the blood and are directly related to progression of atherosclerosis.

- High-density lipoproteins (HDLs) promote cholesterol removal. Thus, the elevation of HDLs reduces the risk for ASCVD.

Atherogenic dyslipidemia can be modified by lifestyle therapy, and if the patient’s ASCVD risk is high, then statins should be initiated.5

When to Screen for High Cholesterol

The decision to screen for high cholesterol is based on the probability of the risk for a cardiovascular event that is high enough to justify therapy for primary prevention.5-7In deciding when to initiate lipid screening, the clinician should consider patients to be at higher risk if they have more than 1 risk factor (eg, hypertension, smoking, and family history) or a single risk factor that is severe. For example, a patient who has several siblings with coronary heart disease in their 40s or a patient who has a very heavy smoking history could be considered at higher risk even though only a single risk factor is present. These patients may benefit from earlier lipid screening and treatment than the broader population.7The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that men at higher risk should undergo lipid screening at age 25, while higher- risk women should undergo screening at age 35. Screening for men and women at lower risk can be initiated at ages 35 and 45, respectively.7

High Cholesterol Prevention and Treatment

Unlike the 2004 ACC/AHA guidelines, which targeted specific cholesterol goals, the 2013 guidelines focus on the importance of treating high cholesterol. Lifestyle modifications are essential in the treatment of dyslipidemia and, when indicated, statin therapy should complement lifestyle changes.4The 2013 guidelines also recommend statins for patients at high risk for ASCVD.7

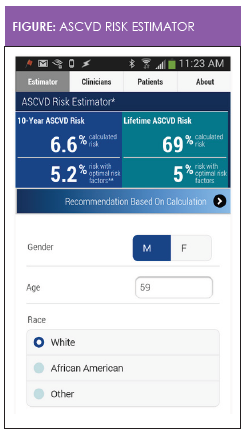

The ACC/AHA’s ASCVD Risk Estimator is a free smartphone app that enables clinicians and patients to estimate 10-year and lifetime risks for ASCVD (Figure). This downloadable tool is intended for use in patients in whom ASCVD is not present and whose LDL cholesterol level is less than 190 mg/ dL.7The 10-year calculated ASCVD risk is a quantitative estimation of the absolute risk based on data from representative population samples. The 10-year risk estimate for “optimal risk factors” represents specific risk factor numbers for an individual of the same age, sex, and race. The optimal risk factors are defined as total cholesterol of 170 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol of 50 mg/ dL, untreated systolic blood pressure of 110 mm Hg, no history of diabetes, and no current tobacco use.7The risk estimate is based on group averages. For example, a 10-year ASCVD risk estimate of 10% means that among 100 patients with the same risk factor profile, 10 would be expected to have a myocardial infarction or stroke in the next 10 years.

Heart-healthy lifestyle habits should be encouraged as primary prevention in all patients. In addition, statins can provide benefit in the form of primary or secondary prevention in the following patient groups7:

- Secondary prevention for patients with known ASCVD

- Primary prevention for patients with a fasting LDL cholesterol level of 190 mg/dL or lower

- Primary prevention for patients with diabetes who are aged 40 to 75 years with a fasting LDL cholesterol level between 70 and 189 mg/dL

- Primary prevention for patients without diabetes who are aged 40 to 75 years and have an estimated 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or higher with an LDL cholesterol level between 70 and 189 mg/dL

Starting Statin Therapy

Among patients with clinical ASCVD (acute coronary syndromes, history of a myocardial infarction, stable or unstable angina, coronary or other arterial revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease), those 75 years or younger without safety concerns should use a high-intensity statin, while a moderate- intensity statin is recommended for those older than 75 years or those with safety concerns. Statin therapy is also recommended as primary prevention in patients with an LDL cholesterol level of 190 mg/dL or higher after secondary causes of hyperlipidemia have been ruled out. In patients 21 years or older with an LDL cholesterol level of 190 mg/dL or higher, a high-intensity statin is recommended to achieve at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol level.7

A moderate-intensity statin is recommended as primary prevention for patients with diabetes who are aged 40 to 75 years and have an LDL cholesterol level of 70 to 189 mg/dL. A high-intensity statin should be considered when the 10-year risk for ASCVD is at or above 7.5%. Statin therapy is also recommended as primary prevention for patients without diabetes who are aged 40 to 75 years with an LDL cholesterol level between 70 mg/dL and 189 mg/dL, estimating the 10-year risk using the ASCVD Risk Estimator. For those not receiving a statin, risk should be estimated every 4 to 6 years. The clinician should engage the patient in a discussion of potential ASCVD risk reduction, drug—drug interactions, and patient preferences. Risk factors and healthy lifestyle habits should be assessed.7

If the patient’s 10-year ASCVD risk is 7.5% or higher, a moderate- or high-intensity statin should be considered. There is less evidence to support moderate-intensity statin use when the 10-year ASCVD risk ranges from 5% to less than 7.5%. Other factors should be considered, such as a family history of premature cardiovascular disease, a high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level of 2.0 mg/L or higher, a coronary artery calcium score of 300 Agatston units or higher, or an ankle-brachial index less than 0.9.7

Statin therapy should be initiated or continued as primary prevention when the patient’s LDL cholesterol level is less than 190 mg/dL and the patient is younger than 40 years or older than 75 years, or the 10-year ASCVD risk is less than 5% when there is evidence of genetic hyperlipidemia, a family history of premature ASCVD, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level of 2 mg/L or higher. The evidence for statin therapy is less clear, but risk factors, adverse reactions, and costs should be used to inform clinical decision making.7

Before initiating or continuing statin therapy, shared decision making—a communication strategy in which the clinician and patient discuss risks and benefits of treatment—should be employed. Communication should include the potential for ASCVD risk-reduction benefits, discussion about living a heart-healthy lifestyle, consideration and management of other risk factors, the potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, and patient preferences. When interventions are determined by degree of risk, shared decision making, and application of clinical guidelines, patient outcomes should improve.

Mary Donnelly-Strozzo is an instructor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing and has worked in adult primary care for the past 45 years. She has expertise in preventive cardiology and leads her own evidence- based research in decreasing cardiovascular risk factors in the urban setting at her practice site. She is a member of the Preventive Cardiovascular Nursing Association.Roseann Velez is a family nurse practitioner who practices in a patient-centered medical home where she precepts student nurse practitioners 2 days a week. Dr. Velez is the only nurse member of the Advisory Council for Immunizations in the state of Maryland. She is also a leader in the Nurse Practitioner Association of Maryland, where she serves as secretary.

References

- Weintraub WS, Daniels SR, Burke LE, et al. Value of primordial and primary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a policy statement from the American Heart Association.Circulation. 2011; 124(8):967-990.

- Arbab-Zadeh A, Nakano M, Virmani R, Fuster V. Acute coronary events.Circulation.2012; 125(9): 1147-1156.

- Collaboration IRGCERF, Sawar N, Butterworth, AS, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 82 studies.Lancet.2012; 379(9822):1205-1213.

- Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation,2014:129(25 suppl 2):S1-45

- Frank, ML Gerhardt, AM (2015). Treating dyslipidemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.The Nurse Practitioner, 40(8), 18-23. Doi-10.1097/01.NPR.0000469253.11367.2c

- Kling JM, Miller VM, Mankad R, et al. Go red for women cardiovascular health-screening evaluation: The dichotomy between awareness and perception of cardiovascular risk in the community.Journal of Women’s Health.2013; 22(3): 210-218.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB Sr, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Robinson J, Schwartz JS, Smith SC Jr, Sorlie P, Shero ST, Stone NJ, Wilson PW. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circulation. 2013;00:000—000.