Supplement Use for Better Health

With thousands of dietary supplements on the market and often contradictory or unconvincing clinical evidence for their use, many providers hesitate to make recommendations for or against them.

With thousands of dietary supplements on the market and often contradictory or unconvincing clinical evidence for their use, many providers hesitate to make recommendations for or against them. In the 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 54% of US adults reported taking at least 1 dietary supplement.1Providers must educate patients about when a supplement is needed, the need to avoid supplements with certain health conditions because of drug interactions, and the appropriate dosage to avoid toxicity.

In 1994, Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, which defined supplements as intended to supplement the diet; containing 1 or more dietary ingredients (including amino acids, herbs or other botanicals, minerals, vitamins, and certain other substances) or their constituents; and intended to be taken by mouth, such as capsules, liquids, powders, supplements, or tablets.2

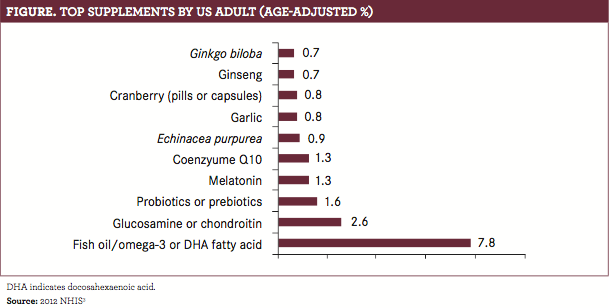

According to the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), adult use of fish oil, melatonin, and prebiotics or probiotics increased, while use of chondroitin/glucosamine, echinacea, and garlic decreased from the 2007 survey data.3Although dietary supplement users were twice as likely to report wellness rather than treatment as a reason for taking supplements, fewer than 1 in 4 reported reduced stress, better sleep, or feeling better emotionally as a result

of using dietary supplements.4Fish oil, which is one of the most extensively researched supplements for many indications, is reported as the most commonly used supplement. (FIGURE).

Although supplements are generally considered low risk with mild adverse effects (AEs), there are important safety considerations to keep in mind before using them. Certain supplements come with their own risks. For example, kava, used for anxiety and sleep, can cause serious damage to the liver.5Supplement—drug interactions also can lead to AEs. For example, antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, can reduce the effectiveness of some types of chemotherapy; garlic can increase the risk of bleeding (no risk in dietary amounts); St John’s wort can increase the metabolism of antidepressants and birth control pills, making them less effective; and vitamin K can reduce the ability of blood thinners to work.6Safety in children has not been established for most supplements.5Despite this, the NHIS study found that 4.9% of children aged 4 to 17 years used natural products, most commonly fish oil,Echinacea purpurea, and melatonin.3

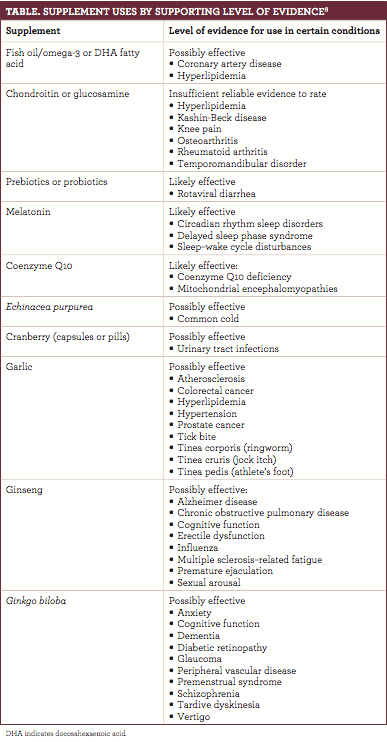

Using supplements for the right reason in the correct amount is essential for safety. There are times where supplements are indicated and may be effective (TABLE), such as during pregnancy, when women need more iron; also, women of child-bearing age benefit from 400 mcg of folic acid to prevent birth defects.6,7To ensure that a patient is not taking too much, check the daily value (DV) on the label. The DV indicates the percent of the reference daily intake or daily reference value of a dietary ingredient that is in a serving of the product.2,5Consistently exceeding the recommended daily limit on supplements has the potential to be harmful. For example, ingesting too much vitamin A can cause headaches and liver damage, reduce bone strength, and cause birth defects, and excess iron causes nausea and vomiting and may damage the liver and other organs.2

When discussing supplement use, it is important to emphasize that supplements are best used under the guidance of a health care professional. Be sure to understand what a patient hopes to achieve with supplement use, and set appropriate expectations based on supporting evidence for the intended use. Some helpful resources include the National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements (ods.od.nih.gov) and the Dietary Supplement Label Database (dsld.nlm.nih.gov/dsld/).

Kathryn Hubbard, PharmD, is completing

a PGY-1 community pharmacy residency at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, and Kroger Pharmacy.

References

1. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS nutrition data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet_nutrition.htm. Updated April 6, 2017. Accessed December 16, 2017.

2. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplements. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements website.ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/DietarySupplements-HealthProfessional/. Updated June 24, 2011. Accessed December 16, 2017.

3. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin, RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002—2012.Natl Health Stat Report.2015;(79):1-16.

4. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Americans who practice yoga report better wellness, health behaviors. NCCIH website.nccih.nih.gov/news/press/11042015. Updated September 24, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017.

5. McQueen CE, Orr KK. Natural products. In: Krinsky DL, Ferreri SP, Hemstreet B, et al.Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care.18th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacist Association; 2015.

6. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Iron: fact sheet for consumers. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements website. ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-Consumer/. Updated February 17, 2016. Accessed December 17, 2017.

7. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplements: what you need to know. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements website. ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/DS_WhatYouNeedToKnow.aspx. Updated June 17, 2011. Accessed December 16, 2017.

8. Therapeutic Research Center. Natural medicines. TRC website. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/. Accessed December 16, 2017.

Knock Out Aches and Pains From Cold

October 30th 2019The symptoms associated with colds, most commonly congestion, coughing, sneezing, and sore throats, are the body's response when a virus exerts its effects on the immune system. Cold symptoms peak at about 1 to 2 days and last 7 to 10 days but can last up to 3 weeks.

COPD: Should a Clinician Treat or Refer?

October 27th 2019The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines the condition as follows: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.â€

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Is Preventable With Proper Treatment

October 24th 2019Cancer, diabetes, and heart disease account for a large portion of the $3.3 trillion annual US health care expenditures. In fact, 90% of these expenditures are due to chronic conditions. About 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, 7 million have undiagnosed diabetes, and 83 million have prediabetes.

What Are the Latest Influenza Vaccine Recommendations?

October 21st 2019Clinicians should recommend routine yearly influenza vaccinations for everyone 6 months or older who has no contraindications for the 2019-2020 influenza season starting at the end of October, according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Pharyngitis?

October 18th 2019There are many different causes of throat discomfort, but patients commonly associate a sore throat with an infection and may think that they need antibiotics. This unfortunately leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing when clinicians do not apply evidence-based practice.