A Futuristic Health Care Approach

Thousands of people struggle to find treatments for various refractory comorbidities.

Thousands of people struggle to find treatments for various refractory comorbidities.

However, the health care system has evolved, and many of these patients can now find their ideal treatments using precision medicine. Precision medicine, a revolutionary way to look at treatment, is an initiative that was promoted extensively during Barack Obama’s presidency.1Instead of a 1-size-fits-all approach, precision medicine considers the patient’s environment, genetic variation, and lifestyle. This is most useful in the oncology setting because of cancer’s numerous genetic variations.2Precision medicine’s goal is to reduce unnecessary “shotgun” approaches to treatment and use the most beneficial medicine for the patient.

How Precision Medicine Differs

The difference between precision medicine and traditional treatment methods is the level of diagnostic testing.3Traditionally, clinicians may use a patient’s symptoms and 1 or 2 tests to diagnose cancer, and then the oncology team may prescribe a broad chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy regimen for the specific cancer. In precision medicine, clinicians select the treatment of choice at a molecular level. For example, if a patient is given a diagnosis of breast cancer, a genetic test after a breast biopsy could reveal that the breast cancer isHER2negative. In this case, palbociclib would be a better option for the patient than trastuzumab because it is effective againstHER2-positive cancer.4Effective genetic testing can pinpoint mutations driving cancer.

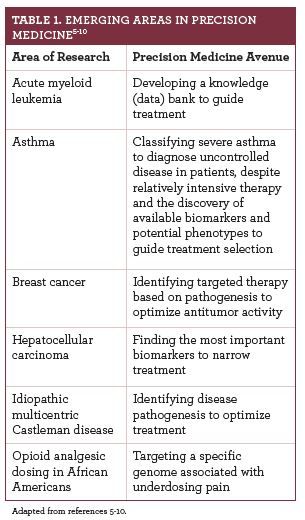

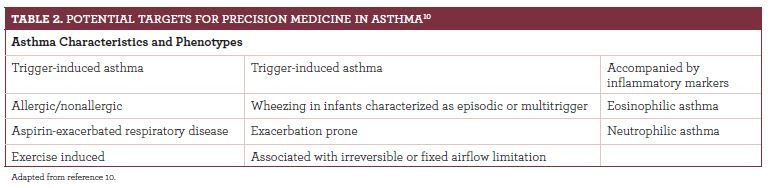

Although precision medicine is most likely to be used in cancer, its application in other areas is growing.Table 15-9lists areas of precision medicine research and the emerging approach in each. Health care providers should note that progress is being made in the use of precision medicine to treat asthma, which has traditionally been treated with products in the retail setting. (Table 2).10

Limitations and Strengths

Precision medicine’s technology is groundbreaking, though current precision tools and technology do not diagnose disease with 100% certainty yet. This area is constantly evolving, and biotechnology companies are developing increasingly more accurate technologies.2To better analyze data gathered from tests, the collective scientific community must develop comprehensive databases using enormous patient populations. Investigators and statisticians need to secure these databases of personal health information and ensure patients’ confidentiality and privacy. These obstacles make it very difficult for precision medicine to be implemented widely, but the largest barrier is the cost of the tests involved.

Cancer is a financially burdensome disease. Diagnostic testing, doctor appointments, and drug treatments all cost a pretty penny. Adding precision medicine to these expenses could be too much for most families. A commercial test of 300 genes can cost $5800, and clinical whole exome testing, in which all genes encoding proteins in a genome are sequenced, can cost $1000 to $5000 per test.3The tests, which are usually narrower in scope than those cited here but still costly, typically use tumor biopsy tissue. Within a tumor, cells are diverse, and the genetic composition of cells from one area of the tumor may differ compared with that of cells in another area.11A genome test using a small part of this tumor could omit vital information or show no new information, making drug selection impossible or incorrect. The cost for the under- or uninsured patient can be thousands of dollars. Thus, identifying a suitable treatment early on to minimize costs is not always possible.

Conclusion

If precision medicine is sometimes ineffective and usually expensive, why is it under exploration? Although precision medicine’s success rate is imperfect, it has tremendous potential and, if refined, can direct care. Quality tests, which are increasing in number, have advanced treatment for breast cancer and melanoma. Precision medicine is a focus for the future. Its cost and efficiency can be implementation barriers, but the hope is that research will bring clinicians to a point where genetic testing can help determine every disease’s ideal treatment.

Zachary M. McPherson is a PharmD candidate at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.

References

- Holst, L. The Precision Medicine Initiative: data-driven treatments as unique as your own body. The White House: President Barack Obama website. obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2015/01/30/precision-medicine-initiative-data-driven-treatments-unique-your-own-body. Published January 30, 2015. Accessed October 9, 2018.

- What is precision medicine? US National Library of Medicine website. ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/precisionmedicine/definition. Published October 30, 2018. Accessed October 30, 2018.

- Tumor DNA sequencing in cancer treatment. National Cancer Institute website. cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/precision-medicine/tumor-dna-sequencing. Published October 5, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Breast cancer - metastatic: types of treatment. Cancer.Net website. cancer.net/cancer-types/breast-cancer-metastatic/types-treatment. Published May 2018. Accessed October 11, 2018.

- Smith AH, Jensen KP, Li J, et al. Genome-wide association study of therapeutic opioid dosing identifies a novel locus upstream of OPRM1.Mol Psychiatry.2017;22(3):346-352. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.257.

- Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, Finn RS. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma.Nat Rev Clin Oncol.2018;15(10):599-616. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4.

- Gerstung M, Papaemmanuil E, Martincorena I, et al. Precision oncology for acute myeloid leukemia using a knowledge bank approach.Nat Genet.2017;49(3):332-340. doi: 10.1038/ng.3756.

- Newman SK, Jayanthan RK, Mitchell GW, et al. Taking control of Castleman disease: leveraging precision medicine technologies to accelerate rare disease research.Yale J Biol Med.2015;88(4):383-388.

- Ju J, Zhu AJ, Yuan P. Progress in targeted therapy for breast cancer.Chronic Dis Transl Med.2018;4(3):164-175. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.04.002.

- Bleecker ER, Panettieri RA Jr, Wenzel SE. Clinical issues in severe asthma: consensus and controversies on the road to precision medicine.Chest.2018;154(4):982-983. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.1022.

- Precision medicine in cancer treatment. National Cancer Institute website. cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/precision-medicine. Updated October 3, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2018.

Knock Out Aches and Pains From Cold

October 30th 2019The symptoms associated with colds, most commonly congestion, coughing, sneezing, and sore throats, are the body's response when a virus exerts its effects on the immune system. Cold symptoms peak at about 1 to 2 days and last 7 to 10 days but can last up to 3 weeks.

COPD: Should a Clinician Treat or Refer?

October 27th 2019The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines the condition as follows: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.â€

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Is Preventable With Proper Treatment

October 24th 2019Cancer, diabetes, and heart disease account for a large portion of the $3.3 trillion annual US health care expenditures. In fact, 90% of these expenditures are due to chronic conditions. About 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, 7 million have undiagnosed diabetes, and 83 million have prediabetes.

What Are the Latest Influenza Vaccine Recommendations?

October 21st 2019Clinicians should recommend routine yearly influenza vaccinations for everyone 6 months or older who has no contraindications for the 2019-2020 influenza season starting at the end of October, according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Pharyngitis?

October 18th 2019There are many different causes of throat discomfort, but patients commonly associate a sore throat with an infection and may think that they need antibiotics. This unfortunately leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing when clinicians do not apply evidence-based practice.