Travel Health

The frequency and scale of global travel has led to unprecedented opportunity for rapid spread of emerging and reemerging diseases.

Introduction

The frequency and scale of global travel has led to unprecedented opportunity for rapid spread of emerging and reemerging diseases. Providers not only need to take measures to protect their patients from health risks, but they must also consider measures to protect the community at large. Clinicians need to be aware of the current health concerns in order to protect the residents in the communities where travelers will be visiting, as well as the residents in the communities to which travelers will be returning.

In order to minimize the spread of nonendemic diseases from region to region and to offer solid pretravel counseling, clinicians should be familiar with resources that identify known and emerging health threats by geographic distribution.1The CDC offers 2 excellent resources that are accessible to health care professionals, travel professionals, and laypersons. The first is theCDC Health Information for International Travel: The Yellow Book. The second is the CDC Travelers’ Health Website (cdc.gov/travel).1Alternatively, there are proprietary software platforms that provide similar information. Such services are not free, but they may simplify and accelerate the process of locating pertinent travel health information by location.

The health needs of travelers vary based on destination, length of stay, planned activities, age and current health status of the traveler, and pregnancy status. Health risks vary according to whether international travel is for business, tourism, family, or humanitarian reasons.2Multiple factors must be taken into account, including costs, because many travel health—related expenses are unlikely to be covered by insurance. Clinicians should be able to help patients prioritize their health concerns, but they should also realize that patients with complex itineraries or preexisting health conditions may require more extensive and personalized planning efforts. In addition, patients who have a complex health history, have young children, or are currently pregnant may need to be referred to a travel medicine specialist.

Pretravel Counseling

These consultations offer clinicians an opportunity to advise patients regarding methods for limiting common travel health hazards and minimizing the risks of contracting illnesses while traveling. It is an opportunity to update routine vaccinations and to provide vaccine recommendations based on travel destination. The pretravel health visit is also the time to discuss disease prophylaxis and self-treatment of common travel illnesses. Clinicians should discuss strategies to avoid food and waterborne illnesses, sexually transmitted infections, mosquito-borne infections, and respiratory tract infections.3If travel health—related costs are an issue, now is also the time to help patients prioritize their health concerns to get maximum benefits within their budget.

Routine Immunizations to Update Before Travel

Finally, clinicians should be aware that Menactra and Menveo, the standard meningococcal vaccines, are only safe for patients up to age 55 years. Travelers 56 years and older should receive Menomune instead.6

Patients should bring their vaccine records to the pretravel consultation. Routine vaccines that should be completed or brought up-to-date before travel includehaemophilus influenzaetype b, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, influenza, measles/mumps/rubella, meningococcal, pneumococcal, polio, rotavirus, tetanus/diptheria/pertussis, varicella, and zoster. For the most part, routine vaccines follow standard US immunization schedules and are covered by health insurance. Therefore, the zoster and pneumococcal vaccines will not be necessary unless the travelers meet the age and health requirements set by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.4The one exception is the meningococcal vaccine. For travelers going to high-risk destinations, the meningococcal vaccine should be administered every 3 to 5 years. And for those attending the Hajj (the annual pilgrimage by Muslims to Mecca), proof of meningococcal vaccine is required in order to be issued a visa. Travelers need a valid International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis documenting that they were given the meningococcal vaccine 10 or more days prior to, and within 3 years of, travel in order to enter Saudi Arabia.5

Travel Immunizations

Patients requiring travel health vaccines for yellow fever, rabies, or Japanese encephalitis may need to be referred to a travel health specialist because many standard health care settings are not equipped to administer them. Additionally, vaccines for cholera and tick-borne encephalitis are not available in the United States. The travel-related vaccines that are more readily available are hepatitis A and typhoid. Hepatitis A is administered as a 2-dose series, with the second dose approximately 6 months after the initial dose. The typhoid vaccine may be given orally or intramuscularly (IM). IM typhoid is inactivated, and one dose given 2 weeks prior to travel offers protection for 2 years. Oral typhoid is a live vaccine and requires 4 doses over 7 days; it should be given at least 1 week prior to travel, and a booster is required every 5 years if typhoid remains a concern. Travelers should know that neither typhoid vaccine (IM or oral) is 100% effective, so they should maintain caution when eating and drinking.7Patients who do not complete vaccines requiring a series (such as hepatitis A or B) should be counselled that they may pick up where they left off and that the series does not need to be restarted.3

Travel Prophylaxis

Altitude sickness is caused by hypoxemia secondary to decreased air pressure. It is caused by climbing mountains or traveling to high-altitude areas, such as Colorado. This consists of 3 distinct syndromes: acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). Both HACE and HAPE are rare but can be fatal. HACE presents with drowsiness, altered mental status, and ataxia. HAPE presents with breathlessness, weakness, and cough. Both require descent to a lower altitude to prevent death. AMS is much more common and not fatal, and presents with head ache, fatigue, nausea, and pallor. The condition usually resolves as the body acclimates to the altitude—generally within 24 to 72 hours.

There are medications to help prevent altitude illness, but providers should stress that proper altitude acclimation remains paramount to avoiding altitude illness. Acetazolamide and dexamethasone are used to help prevent AMS and HACE. Acetazolamide acidifies the blood, causing an increase in respiration and oxygenation. Dosing at 125 mg every 12 hours begins the day before increased altitude. Acetazolamide, however, should be avoided by travelers who are allergic to sulfa drugs. Dexamethasone at 4 mg every 6 hours is an alternative form of treatment.8

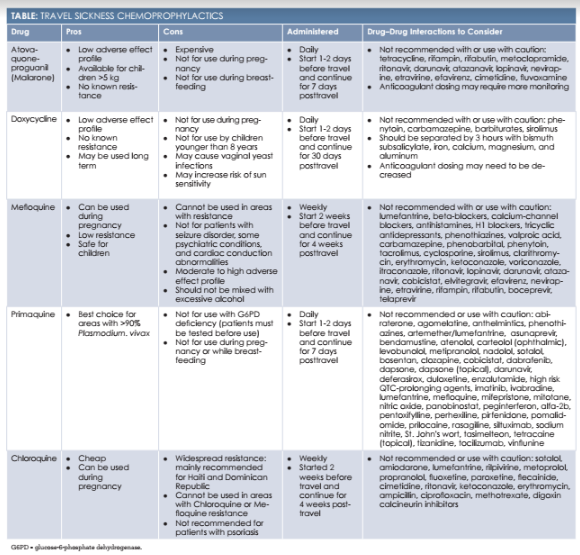

Malaria continues to pose a very serious risk of morbidity and mortality. Travelers visiting malaria-endemic countries should be counseled regarding chemoprophylaxis and malaria transmission to reduce their risk of contracting the disease. Malaria is a concern for travelers visiting certain areas of Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and the South Pacific. Malaria is transmitted via a bite from an infected femaleAnophelesmosquito.

Clinicians should warn that chemoprophylaxis is only part of avoiding illness and that proper mosquito-bite prevention is essential to limiting the risk for mosquito-borne illnesses. Risk levels vary with the season and type of travel planned. Travelers in low-cost, rural settings face a higher risk than do those staying in air-conditioned hotels. Therefore, mosquito repellants (eg, DEET) and other strategies to avoid mosquito bites should be researched and considered.

When choosing an antimalarial drug, multiple factors should be considered, including cost, length of travel, daily versus weekly administration, resistance, and adverse effects. There are currently 5 different antimalarial medications, and each has pros and cons that should be considered on a case-by-case basis.9The Table provides the pros, cons, and dosage overviews of 5 prophylactics available to travelers.

Travel Self-Treatment

Traveler’s diarrhea (TD) is defined as 3 or more loose stools per day with or without cramping and abdominal pain. It is one of the most common travel ailments—affecting 30% to 70% of travelers. TD may be caused by bacteria, viruses, or protozoa, but bacterial TD accounts for 80% to 90% of cases. The standard incubation period for viral and bacterial causes is 6 to 12 hours and for most protozoal pathogens, 1 to 2 weeks. To date, the best antibiotics for empiric treatment of bacterial TD are ciprofloxacin and azithromycin. It should be noted that bacterial resistance to ciprofloxacin is becoming more common and that neither antibiotic will treat protozoal or viral pathogens. For children younger than 18 years, azithromycin remains first-line therapy.11

Motion sickness refers to vestibular disturbances caused by the movement during car, train, sea, or air travel. Women and children (aged 2 to 12 years) are most commonly affected. Treatment mainstays include antihistamines such as Benadryl, Dramamine, meclizine, promethazine, and cyclizine. The scopolamine patch (transdermal) is an alternative for patients who do not want to take daily oral medication. Other options include prochlorperazine and metoclopramide. For children with motion sickness, Dramamine and Benadryl are considered first-line treatment.12

Recent Global Travel Health Concerns

In the past decades, many illnesses have emerged or reemerged that may be spread by international travelers. Two new respiratory illness caused by coronavirus and characterized by severe pneumonia are Middle East Respiratory Virus (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). New strains of influenza A have also caused global concern, and both H1N1 and H5N1 have caused significant morbidity and mortality.

Several mosquito-transmitted illnesses, such as malaria, West Nile virus, and dengue fever, have long presented serious health risks for travelers, but new mosquito-borne illnesses have also emerged, such as chikungunya and Zika virus. In the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, a new strain of cholera that appears related to strains from Africa and Asia appeared. This strain has now spread to the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and parts of Mexico.

Although rare in the Western Hemisphere, polio continues to circulate in some regions of the world. Recently, polio has been identified in Pakistan, Syria, Somalia, Iraq, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea. Finally, measles outbreaks continue throughout the world due to lack of vaccination.13

Posttravel Assessment

When a patient presents with an illness that may be related to travel, the clinician should consider factors such as severity of illness, vaccine record, past medical history, type of travel, accommodations and activities, insect bites, animal bites, exposure to freshwater from lakes or rivers, source of drinking water, and known exposure to illness. Febrile illnesses should be viewed as highly suspicious, especially with respiratory illness, rash, and/or nervous system involvement.14

Conclusion

Clinicians have many facets to consider during the travel health visit. Travelers should be made aware of known health risks specific to their destination to ensure the safest travel possible. Clinicians should advise travelers regarding recommended vaccines, chemoprophylaxis, and self-treatment options. They must also stress the importance of common wellness measures, such as clean drinking water, mosquito protection, sun protection, condom use, and safe eating practices. Travelers should be directed to reputable travel health resources and encouraged to take an active part in preparing and protecting themselves during their travels.1,2

Felicia Spadini is a board-certified nurse practitioner. She began her career as a registered nurse in emergency medicine and then worked in the cardiothoracic stepdown unit for several years as a certified diabetes resource nurse and a certified wound/skin care nurse. As a nurse practitioner, she has worked in the retail health care setting since graduating in 2013. Her passion is research and providing education for peers and patients alike.

References

- Lee A, Kozarsky P. introduction to travel health & the yellow book. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 2-5

- Sotir A, LaRocque R. travel epidemiology. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 11-14

- Kroger A, Strikas R. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 42-53

- Chen L, Hochberg N, Magill A. the pre-travel consultation. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 28-35

- Bowron C, Maalim S. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 490-495

- MacNeil J, Meyer S. meningococcal disease. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 263-267

- Newton A, Routh R, Mahon B. typhoid and paratyphoid fever. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 336-339

- Hackett P, Shlim D. altitude illness. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 67-72

- Arguin P, Tan K. malaria. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 236-255

- Youngster I, Barnett E. interactions among travel vaccines & drugs. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 54-57

- Connor B. self-treatable conditions: travelers’ diarrhea. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 28-35

- Erskine S. self-treatable conditions: motion sickness. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 76-78

- Ostroff S. the role of the traveller in translocation of disease. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 15-21

- Fairly J. post-travel evaluation. In:Brunette G, ed.CDC Health Information For International Travel The Yellow Book 2016. Atlanta, GA; 2016: 496-500