The Saga of the Sore Throat

As students prepare to return to school, parents are busy coordinating rides, buying school supplies, and attending fun school activities. However, they are also concerned about their children’s increased exposure to illness while in school. In the retail setting, one of the most common complaints assessed during this time of year is a sore throat.

There are many etiologies for sore throat, most of which are viral. Patients and their parents typically present to the clinic because they want to make sure they are not infected with group Astreptococci(GAS). GAS is the cause of sore throat in 15% to 30% of cases in children and 5% to 10% of cases in adults.1Although the likelihood is that the majority of the patients concerned about strep throat will not have it, it can be challenging for clinicians to balance the expectation of patients with the appropriate clinical guidelines to avoid antibiotic resistance. The most effective way to responsibly treat a patient while maintaining a great customer experience is by using the tools available for appropriate diagnosis coupled with clear patient education.

Antibiotic Stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship is a key component to decreasing and preventing antibiotic resistance.2One of the ways we, as an industry, can support the avoidance of antibiotic resistance is by following national guidelines when they are established. The National Guideline Clearinghouse, published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is a collection of guidelines from many different societies, organizations, and disciplines that has been rigorously reviewed and that adhere to the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations as to what makes a guideline trustworthy.3From this collection of information, the AHRQ goes on to develop quality metrics that evaluate clinical adherence to these guidelines, which are published in the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse.4Finally, through the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, which collects data from insurance claims, states can receive unbiased information on how well medical practices are adhering to the guidelines and can publish this data publically. Information for medical practices in Minnesota, for example, can be found at www.mnhealthscores.org/. When it comes to a sore throat, national guidelines emphasize the importance of only prescribing antibiotics when it is appropriate.

Early Antibiotic Therapy

The goal of early antibiotic therapy for GAS is specifically to prevent rheumatic fever, although the added benefit of decreased duration of illness is also clear. Current point-of-care tests only screen for GAS; other strains of strep are likely to resolve on their own and do not carry the same risk of complications. If a point-of-care test is unavailable, or is negative, it is recommended that a throat culture be sent to a lab where the bacteria are left to grow on a plate to determine the presence of GAS. Rapid strep tests and throat cultures are 90% to 95% accurate, however. Accuracy for both tests is dependent on the collection technique of the practitioner.

The practitioner should make sure the patient has not had anything to eat or drink, or used any antiseptic mouthwash prior to having the throat swabbed. Both tonsils must be swabbed, focusing on collecting any obvious pus. In many cases, the patient may gag or express discomfort during or after specimen collection; however adequate sample collection is critical for the accuracy of either test. In the event a patient does not have tonsils, collection should be focused on the back of the throat, which, if done correctly, will likely elicit a gag reflex. Empiric treatment of sore throats is not recommended, and strep testing should not be omitted based on a poor level of cooperation by the patient.

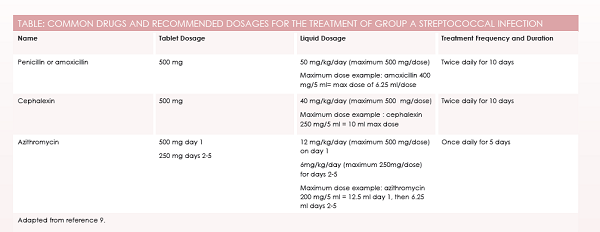

Once an accurate diagnosis of GAS is made, the preferred treatment is penicillin or amoxicillin. The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) published this recommendation in 2012, along with guidance on alternatives when needed.3In patients with a nonsevere allergy to penicillin, a first-generation cephalosporin such as cephalexin is recommended. A patient with a previous anaphylactic reaction to penicillin can be treated with azithromycin for 5 days.

It is important to note that IDSA published an erratum to the initial recommendations to indicate that dosage with azithromycin should be 12 mg/kg/day on day 1, then 6 mg/kg/day on days 2 through 5, rather than 12 mg/kg/day for 5 days straight.4Unfortunately, whereas many guidelines cite the IDSA report as evidence to support the 12 mg/kg/ day dosing for 5 days, they often cite the original article and not the erratum subsequently published (seeTable).

Antibiotic Education

Education on taking the antibiotic as prescribed and for the full duration of 5 or 10 days should be undertaken when treating GAS. There is no need to prophylactically treat members of the same household, but they may consider being evaluated in the future if they begin to have symptoms. The infected patient will be highly contagious for 24 hours once starting the antibiotic. After that time, the amount of bacteria left in the throat, although still requiring eradication with the antibiotic, is not significant enough to be contagious. Symptoms are expected to quickly subside within 2 to 3 days of initiating the antibiotic; if they do not, the patient should follow up for further evaluation. There are mixed reports on how accurate a rapid strep test is after a patient has recently been treated for strep.5,6In these cases, the practitioner may decide to run a throat culture alone or in addition to a rapid strep test.

The patient will want to disinfect or replace anything that is put in the mouth for an extended period of time (eg, toothbrushes, retainers, mouth guards). Symptomatic relief with acetaminophen and ibuprofen can be used in addition to salt water gargles to reduce tonsillar swelling.

Negative Strep Tests

Patients with negative strep tests likely have a viral infection where antibiotics, therefore, will not improve symptoms. Education should focus on symptom relief as well as setting the expectation as to how long the patient may feel sick. Interventions, such as warm liquids; pain medication, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen; and salt water gargles are all key components to symptom relief. A small study indicated the benefits of a throat-coating herbal tea for symptom relief with viral pharyngitis.7Mononucleosis should also be ruled out as a potential infection; however, point-of-care mono tests rely on detection of heterophile antibodies in the blood, which may or may not be present with acute mononucleosis.8

Courtney Ballina became a convenient care clinician in 2012 after graduating from Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, Minnesota, with her family nurse practitioner degree. She is currently a lead nurse practitioner for Target. In addition to continuing to practice within Target Clinics, Courtney also manages the clinical guidelines and training for all new and existing services. She is also responsible for Target’s nurse practitioner externship program and the Clinical Practice Advisory Council. She is currently pursuing her doctorate of nursing practice degree at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama.

References

1) Khan ZZ, Salvaggio MR. Group A streptococcal infections. Medscape website. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/228936-overview. Updated August 21, 2014.

2) Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Diseases Society of America and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS).Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):322-327. doi: 10.1086/665010.

3) Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2012;55(10):e86-e102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

4) Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Dosage error in article text.Clin Infect Dis.2014;58(10):1496.

5) Sheeler RD, Houston MS, Radke S, Dale J, Adamson SC. Accuracy of rapid strep testing in patients who have had recent streptococcal pharyngitis.J Am Board Fam Pract.2002;15(4):261-265.

6) Johnson DR, Kaplan EL. False-positive rapid antigen detection test results: reduced specificity in the absence of group A streptococci in the upper respiratory tract.J Infect Dis.2001;183(7):1135-1137.

7) Brinckmann J, Sigwart H, van Houten TL. Safety and efficacy of a traditional herbal medicine (Throat Coat) in symptomatic temporary relief of pain in patients with acute pharyngitis: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study.J Altern Complement Med.2003;9(2):285-298.

8) Epstein-Barr and infectious mononucleosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.www.cdc.gov/epstein-barr/laboratory-testing.html. Updated January 7, 2014.

9) Haymarket Media Inc. Monthly prescribing reference, version 5.2.1.49; 2015 [mobile application software]. New York, NY; Haymarket Media Inc.