Psoriasis: Diagnosis and Treatment Review

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects primarily the skin and joints.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects primarily the skin and joints.1The condition is triggered and worsened by some medications, infections, skin trauma, obesity, and stress, and those suffering from psoriasis are at higher risk for both cardiovascular disease and depression.1Below is a review and update on the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of psoriasis.

TYPES

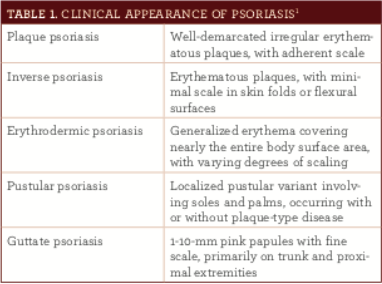

There are 5 types of psoriasis, and patients may present with more than 1 type.1Those are plaque psoriasis, intertriginous psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, and guttate psoriasis.

- Plaque psoriasis, which presents as well-defined, sharply demarcated erythematous plaques, affects 80% to 90% of patients with psoriasis. Of those affected by plaque psoriasis, 80% have a mild presentation, whereas 20% have a moderate-to-severe presentation, meaning that it affects crucial body regions, including the hands, feet, face, or genitals.1

- Intertriginous psoriasis, also commonly referred to as inverse psychosis or flexural psoriasis, presents as erythematous plaques, with minimal scale and lesions within the skin fold.1

- Erythrodermic psoriasis, which is considered a life-threatening emergency, refers to generalized erythema, covering almost the entire surface area of the patient’s body. It is sometimes associated with electrolyte imbal- ances, high-output cardiac failure, hypoalbuminemia, and hypothermia.1,2

- Pustular psoriasis appears as monomorphic sterile pustules on painfully inflamed skin. It often covers the patient’s soles and palms, and it may or may not accompany palmoplantar psoriasis. Pustular psoriasis includes von Zumbusch psoriasis, which includes widespread pustules resulting from fever and toxicity.1

- Guttate psoriasis affects fewer than 2% of those suffering from psoriasis and appears as dew-drop-like salmon-colored papules with a very fine scale. This type of psoriasis often follows a group A streptococcal pharyngitis infection and is more common in children and adolescents than in adults.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Psoriasis typically presents before age 40 and affects males and females equally.2About 2% of the US population is afflicted, with an incidence in adults of about 14 per 10,000.3Without a family history of psoriasis, the risk of developing it is about 4%. However, the risk increases to 28% and 65%if 1 or both parents, respectively, are affected.4

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for developing psoriasis include taking medications, weight gain, smoking, and infection. In addition, alcohol abuse, cold weather, stress, HIV, and postpartum hormonal changes can trigger or exacerbate psoriasis.1,5Medications that most commonly induce or worsen psoriasis include beta-blockers, lithium, indomethacin, tetracyclines, and synthetic anti-malarials.6Other medications that have some evidence suggesting that they may induce or worsen psoriasis include doxycycline, amoxicillin, ampicillin, penicillin, amiodarone, clonidine, digoxin, quinidine, fluoxetine, olanzapine, and benzodiazepine.6

ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS

Other conditions associated with psoriasis include psoriatic arthritis, which occurs in 25% of patients with psoriasis and typically affects the hands and feet.2Furthermore, psoriasis increases a patient’s risk for a variety of mental health conditions including depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.2Research suggests that nearly 60% of patients with psoriasis also suffer from depression.1Psoriasis also increases a patient’s risk for metabolic syndrome, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, lymphoma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.2

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL PRESENTATIONS

Patients typically have skin lesions that are erythematous, scaly patches, papules, or plaques on the extensor surfaces of their hands, feet, scalp, trunk, and/or buttocks.1These skin lesions may or may not be itchy and painful.

The presentation for psoriasis is typically chronic, though it may have a waxing and waning course.2Sometimes lesions can occur after trauma, which is called the Koebner phenomenon.2The clinician should ask about recent medication use as well as recent group A streptococcal upper respiratory infection, which often proceeds guttate psoriasis.1In addition, assess for alcohol and tobacco use as well as a family history of psoriasis.2

During the physical assessment, focus on the skin and head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT). The general physical should look for toxic signs such as fever, hypothermia, and/or dehydration.2The HEENT assessment should look for facial lesions, though these are uncommon, except on the scalp and forehead.2Oral symptoms might be found on the tongue.2

The skin assessment should focus on the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, buttocks, trunk, and scalp.1Other sites that may have lesions include the genitals, the palms and soles, and skin folds.1Also look for sebopsoriasis, greasy scales found on the nasolabial folds and eyebrows as well as Woronoff ring, a circle of pale skin surrounding a psoriatic plaque.1The common physical findings for each type of psoriasis are as follows1:

- Plaque psoriasis presents as well-demarcated round to oval-shaped lesions that vary in size from 1 to several centimeters. The smaller plaques often merge to form larger lesions on the trunk and legs. Plaque psoriasis appears symmetrical on the scalp, trunk, buttocks, and limbs as well as the extensor surfaces of the knees, elbows, and genitals. The scale appears dry, thin, and silvery white. Pinpoint bleed, called the Auspitz sign, happens when the scale is removed. The patient often reports painful fissuring over joints.

- Intertriginous psoriasis presents as erythematous plaques, with much less scaling than plaque psoriasis. Inverse psoriasis is found in the axillary, genital, perineal, and inframammary skin folds.

- Erythrodermic psoriasis, as mentioned above, presents as generalized erythema that covers almost the entire body with varying amounts of scaling.

- Pustular psoriasis appears on the soles and palms, with small sterile pustules.

- Guttate psoriasis appears as dew-drop-shaped, salmon-colored papules with fine scale. They are most often located on the trunk and proximal extremities.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is made based on the clinical appearance (table 1).1,2Typically, the severity of psoriasis is measured by the amount of body surface area affected. Mild-to-moderate psoriasis affects less than 5% of the patient’s body surface area and does not affect their hands, feet, face, and genitals. Moderate-to-severe psoriasis affects greater than 5% of the patient’s body surface area or affects their hands, feet, face, and genitals. A biopsy is rarely needed for confir- mation of the diagnosis.7

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

For plaque psoriasis, the differential diagnosis should include atopic dermatitis (history of hay fever or asthma), contact dermatitis (no silvery scale), lichen planus (involves the wrist and ankles with less scale), seborrheic dermatitis (greasy scale), onychomycosis, tinea corporis (thinner scale with positive potassium hydroxide preparation), pityriasis rosea, and mycosis fungoide (less distinct lesion borders).2,7For guttate psoriasis, the differential diagnosis should include sec- ondary syphilis, which presents with red-brown lesions on the palms of the patient’s hands and the soles of the patient’s feet.2For erythrodermic psoriasis, the differential diagnosis should include drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.2,7Finally, with pregnant women, evaluate for impetigo herpetiformis, also called pustular psoriasis of pregnancy.7

TREATMENT

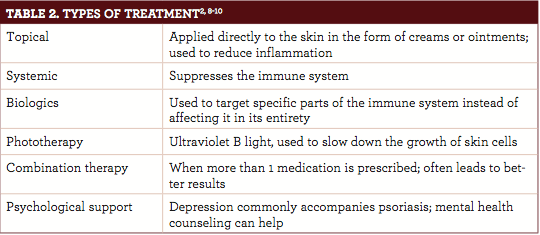

Patient preferences and the ability to adhere to treatment (table 2) are important when choosing therapy. Psoriasis treatment for pregnant women includes topical steroids, followed by phototherapy if necessary. Specific treatment options for each type of psoriasis are listed below.2,8-10

- Plaque psoriasis is typically treated with either topical medications or phototherapy. Emollient should be encouraged for all patients to restore the cutaneous barrier function. Effective topicals include corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, tazarotene, dithranol, and coal bars. Phototherapy, specifically ultraviolet B radiation, is ideal for treating plaque psoriasis that affects greater than 10% of the body’s surface.

- Intertriginous psoriasis should be treated with a low-to-mid—potency topical steroid for less than 4 weeks. Long-term treatment might include calcipotriol, topical immunomodulators, or antimicro- bial therapy.

- Erythrodermic psoriasis should be treated systemically with cyclosporine, infliximab, acitretin, or methotrexate.

- Pustular psoriasis should be treated with acitretin, though this is contraindicated in women of childbearing potential. Other treatments for pustular psoriasis include cyclosporine, methotrexate,and infliximab.

- Guttate psoriasis should be treated with phototherapy or a tonsillectomy.

As mentioned above, depression is often comorbid with psoriasis. It is important to both recognize and treat the depression, as well, because this can lead to poor adherence to treatment regimens and a lower overall quality of life. Consider referring these patients to mental health counseling in addition to treating their psoriasis.

ICD-10 CODES

L40 psoriasis

- L40.0 psoriasis vulgaris

- L40.1 generalized pustular psoriasis

- L40.2 acrodermatitis continua

- L40.3 pustulosis palmaris et plantaris

- L40.4 guttate psoriasis

- L40.5 arthropathic psoriasis—use also o M07.0 distal interphalangeal psoriatic arthropathy. o M07.1 arthritis mutilans o M07.2 psoriatic spondylitis o M07.3 other psoriatic arthropathies o M09.0 juvenile arthritis in psoriasis

- L40.8 other psoriasis

- L40.9 psoriasis, unspecified

- L41 parapsoriasis o L41.0 pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta o L41.1 pityriasis lichenoides chronica o L41.2 lymphomatoid papulosis o L41.3 small plaque parapsoriasis o L41.4 large plaque parapsoriasis o L41.5 retiform parapsoriasis o L41.8 other parapsoriasis o L41.9 parapsoriasis, unspecified

Melissa DeCapua, DNP, PMHNP-BC

, is a psychiatric nurse practitioner with a clinical background in psychosomatic medicine. She now works as a design researcher in

the technology industry, guiding product development by combining her clinical expertise and creative thinking. She is a strong advocate for empowering nurses, and she fiercely believes that nurses should play a pivotal role in shaping modern health care. For more about Dr. DeCapua, visit her website at melissadecapua.com and follow her on Twitter @melissadecapua.

References

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):826-850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7.

- Huerta C, Rivero E, Rodríguez LA. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population.Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(12):1559-1565. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1559.

- 4. Swanbeck G, Inerot A, Martinsson T, et al. Genetic counselling in psoriasis: empirical data on psoriasis among first-degree relatives of 3095 psoriatic probands. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(6):939-942.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):451-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.027.

- Basavaraj KH, Ashok NM, Rashmi R, Praveen TK. The role of drugs in the induction and/or exacerbation of psoriasis.Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(12):1351-1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04570.x.

- Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidence-based guide for primary care.J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(6):787-801. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.130055.

- Canadian Psoriasis Guidelines Committee. Canadian guidelines for management of plaque psoriasis. http://dermatology.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/cdnpsoriasisguidelines.pdf. Published June 2009. Accessed July 11, 2017.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 5. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(1):114-135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.026.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 3. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):643-659. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.032.