Avoiding Drug–Drug Interactions in Patients With Respiratory Diseases

An incredible number of diseases and infections warrant the use of respiratory medications. Retail health prescribers write prescriptions for numerous respiratory medications for this handful of disease states in diverse patient populations.

An incredible number of diseases and infections warrant the use of respiratory medications. For example, in 2009, 1 in 12 people in the United States had asthma. Asthma has increased in prevalence annually across all ages, genders, and racial groups, costing billions of dollars in medical expenses and missed school and work days.1,2According to the COPD Foundation, 6.3% of Americans have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).3The prevalence of allergic diseases has also risen worldwide. In the United States, 7.8% and 13.0% of adults report having hay fever and sinusitis, respectively.4Retail health prescribers write prescriptions for numerous respiratory medications for this handful of disease states in diverse patient populations. With such widespread use of medications, how can prescribers avoid drug—drug interaction (DDI) incidents?

DDIs

An interaction is a reciprocal action or influence. All substances that people apply or consume, including drugs, food, and supplements, can potentially interact.5A DDI is the influence of drugs on each other, pharmacokinetically (ie, the body exerts effects on drugs), and pharmacodynamically (ie, drugs exert effects on the body). Major DDI categories involve the excretion and/or metabolism of 1 or all drugs in the relationship.6A major route of metabolism is cytochrome P450 (CYP) hepatic enzyme action.

RESPIRATORY DDIs

When respiratory medications are used appropriately, few DDIs occur. Many “major” interactions are magnified adverse events. Main interactions between many types of respiratory drugs are additive effects, commonly found with anticholinergic drugs and QTc interval—prolonging drugs.7,8

Other DDIs produce antagonistic effects. For example, beta-agonists, found in many inhalers, cause bronchodilation, while beta-block- ers cause bronchoconstriction. Patients who take beta-blockers may require more inhaler doses to achieve desired outcomes because the drugs work against each other. Nonselective beta-blockers that influence both the cardiac and respiratory muscles are contraindicated with beta-agonist medications. Cardioselective beta-blockers work preferentially on cardiac muscles, with limited respiratory effects at low doses. Selective beta-blockers develop cardiac, nonselective, and respiratory effects as doses increase.9Table 1 lists noteworthy respiratory medication DDIs.7,10-18

CONDITIONS REQUIRING RESPIRATORY MEDICATIONS

With a large portion of the population using respi- ratory medications, patients with comorbidities are common. Respiratory medications are also often used for secondary conditions. Subsequently, pre- scribers use respiratory medications in conjunction with many medication classes. Common medications include those for:

- Allergies, such as antihistamines and decongestants11-14,18

- Asthma, such as antimuscarinics, beta-agonists, cromolyn, epinephrine, immune modulators, leukotriene-receptor modulators, steroids, and theophylline11,20,21

- Bronchitis, such as antitussives, decongestants, expectorants, and mucolytics22,23

- COPD, such as antibiotics, antimuscarinics, beta-agonists, roflumilast, steroids, and theophylline24

- Cystic fibrosis, such as antibiotics, cystic fibrosis trans- membrane regulator modulators, mucolytics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs25,26

- Pneumonia, such as antibiotics, including β-lactams, doxycycline, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides;27,28These medications are not ideal for all respiratory disease states and may be contraindicated.

Roflumilast is used for patients with COPD but not recommended for patients with asthma.14Leukotriene-receptor modulators and mast cell stabilizers are useful for asthma but not recommended for COPD.11,20,21,24Corticosteroids should never be used in patients with cystic fibrosis.25,26These considerations are important when treating patients with comorbidities, especially multiple respiratory diseases.

Smoking cigarettes can influence respiratory disease development and exacerbations. Smoking cessation is recommended for all patients but critical for those with respiratory diseases. Smoking cessation products also have the potential to create DDIs. Additionally, cigarette smoke induces several cytochrome P450 enzymes, notably CYP 1A2. Medications metabolized by CYP 1A2 will have shorter durations of action.15,29,30

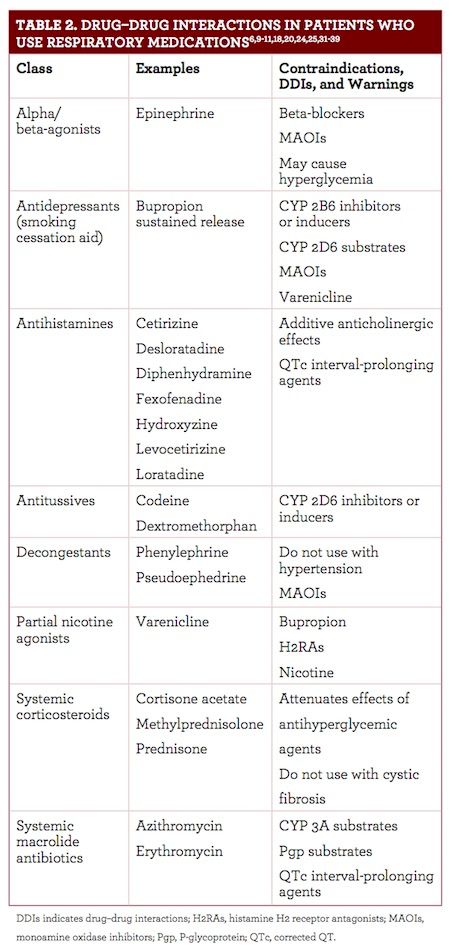

Table 2 notes specific DDIs that can occur in patients who use respiratory medications frequently.6,9-11,18,20,24,25,31-39

Prevent medication errors and potential DDIs by building counseling and medication reconciliation into the practice.

Results from studies have shown that most patients use inhalers incorrectly.40,41Review how to use respiratory medications such as inhalers with patients regularly. Educate them about proper use to prevent adverse reactions and errors.

Reassess all medications that patients take each visit to reduce additive or antagonistic reactions. Multiple prescribers may prescribe similar medications or make overlapping recommendations. Many patients must be prompted to disclose all prescription and OTC medications, supplements, and vitamins that they use. Patients may not consider vitamins important or share only the medications pertaining to a specific prescriber. As noted, all substances that patients put in or on their bodies have the potential to interact. Medication counseling and reconciliation can reduce the possibility of unknown interactions and adverse effects.

CONCLUSION

The potential for DDIs exists among all medications. The probability of interactions increases and decreases based on medication classes and the individual patient. Retail health providers can spot and prevent these interactions before they occur. Although respiratory medications are associated with few DDIs, patients who use respiratory medications may be on countless other drugs. Practicing medication reconciliation will help avoid DDIs, providing better care for patients.

Kelsey Fontneau is a PharmD candidate at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy in Storrs.

References

- Asthma in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. cdc.gov/vitalsigns/asthma/index.html. Updated March 3, 2011. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- Asthma facts and figures. aafa.org/page/asthma-facts.aspx. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America website. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- COPD statistics across America. COPD Foundation website. copdfoundation.org/What- is-COPD/COPD- Facts/Statistics.aspx. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- Allergy statistics. aaaai.org/about-aaaai/newsroom/allergy- statistics. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology website. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- Interaction. Merriam-Webster website. merriam-webster.com/dictionary/interaction. Accessed January 16, 2018.

- Drug interactions: what you should know. US Food and Drug Association website. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/ucm163354.htm. Updated September 25, 2013. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- Horn JR, Hansten PD. Cholinergic-anticholinergic drug interactions.Pharm Times. pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2005/2005-08/2005- 08-9764. Published August 1, 2005. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- Nachimuthu S, Assar MD, Schussler JM. Drug-induced QT interval prolongation: mechanisms and clinical management.Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2012;3(5):241-253. doi:10.1177/2042098612454283.

- Short PM, Williamson PA, Anderson WJ, Lipworth BJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial to evaluate chronic dosing effects of propranolol in asthma.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(12):1308-1314. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2206OC.

- Horn JR, Hansten PD. Inhaled corticosteroids: watch for drug interactions.Pharm Times. pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2004/2004-09/2004- 09-4539. Published September 1, 2004. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- Pruitt B. Pharmacologic treatment of respiratory disorders.RT Mag. rtmagazine.com/2007/05/pharmacological-treatment- of-respiratory- disorders/. Published May 3, 2007. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- AAAAI allergy and asthma drug guide. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology website. aaaai.org/conditions-and- treatments/drug-guide. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- Allergy treatment. American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology website. acaai.org/allergies/treatment. Accessed January 10, 2018.

- Allergy treatment. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America website. aafa.org/page/allergy-treatments.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2018.

- Quibron-T [prescribing information]. Bristol, TN: Monarch Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2006. druglib.com/druginfo/quibron-t- sr/indications_dosage/. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Daliresp [prescribing information]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2013. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022522s003lbl.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Bronchodilators. National Health Service in England website. nhs.uk/conditions/bronchodilators/. Updated October 5, 2016. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- Antimuscarinic drugs.Nurs Times. nursingtimes.net/antimuscarinic-drugs/200030.article. Published September 1, 2004. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- Seasonal allergies: nip them in the bud. Mayo Clinic website. mayoclinic.org/diseases- conditions/hay-fever/in- depth/seasonal-allergies/art- 20048343. Published December 29, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- 2017 pocket guide for asthma management and prevention. Global Initiative for Asthma website. ginasthma.org/2017-pocket- guide-for- asthma-management- and-prevention/. Accessed January 10, 2018.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Asthma care quick reference, diagnosing and managing asthma. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthma_qrg.pdf. Updated September 2012. Accessed January 10, 2018.

- Bronchitis. Mayo Clinic website. mayoclinic.org/diseases- conditions/bronchitis/diagnosis-treatment/drc- 20355572. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- Kinkade, S, Long NA. Acute bronchitis.Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(7):560-565.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. GOLD 2017 global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. goldcopd.org/gold-2017- global- strategy-diagnosis- management-prevention- copd/. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- About cystic fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation website. cff.org/What-is- CF/About- Cystic-Fibrosis/. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- Chronic medications to maintain lung health clinical care guidelines. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation website. cff.org/Care/Clinical-Care- Guidelines/Respiratory-Clinical- Care- Guidelines/Chronic-Medications- to-Maintain- Lung-Health- Clinical-Care- Guidelines/. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- Mandell, LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27-S72. doi: 10.1086/511159.

- Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61- e111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353.

- Brody JE. No such thing as a healthy smoker.New York Times. June 16, 2016. well.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/06/20/no-such- thing-as- a-healthy- smoker/. Accessed January 9, 2018.

- Hukkanen J, Jacob P 3rd, Peng M, Dempsey D, Benowitz NL. Effect of nicotine on cytochrome P450 1A2 activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(5):836-838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04023.x.

- Zyban [prescribing information]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/020711s044lbl.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Avoiding drug interactions. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm096386.htm. Updated November 27, 2018. Accessed January 25, 2018.

- Olasińska-Wiśniewska A, Olasiński J, Grajek S. Cardiovascular safety of antihistamines. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31(3):182-186. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.43191.

- Delsym [prescribing information]. Parsippany, NJ: Reckitt Benskiser; 2014. iodine.com/drug/delsym/fda-package- insert. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Codeine [prescribing information]. Eatontown, NJ: West-Ward Pharmaceuticals Corp; 2017. online.lexi.com/lco/medguides/647259.pdf.Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Hasselbring B. How will decongestants interact with other kinds of drugs? How Stuff Works website. health.howstuffworks.com/diseases-conditions/allergies/allergy- treatments/how-will-decongestants-interact- with-other- kinds-of- drugs.htm. Accessed January 25, 2018.

- Chantix [prescribing information]. New York, NY: Pfizer Laboratories, Division of Pfizer Inc; 2016. labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=557. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Zithromax [prescribing information]. New York, NY: Pfizer Laboratories, Division of Pfizer Inc; 2017. labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=511. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Erythromycin Tablets, film-coated tablets [prescribing information]. Atlanta, GA: Arbor Pharmaceuticals LLC; 2013. dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=ca1326d6- c5c6-4572- 96b6-e56cd944799c. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Hanania N. In COPD, medication delivery matters. American College of CHEST Physicians website. chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2017/12/In- COPD- Medication-Delivery- Matters. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Lehman S. Most people use inhalers and auto-injectors improperly. Reuters website. reuters.com/article/us-health- devices-asthma- allergy/most-people- use-inhalers- and-auto- injectors-improperly- idUSKBN0K213420141224. Published December 24, 2014. Accessed January 16, 2018.