Ascultating Breath Sounds: What the Retail Clinician Should Know

Most patients experience respiratory distress symptoms at some point in their lives, and at times, those symptoms will drive them to seek a health care provider’s diagnosis at a retail clinic.

Most patients experience respiratory distress symptoms at some point in their lives, and at times, those symptoms will drive them to seek a health care provider’s diagnosis at a retail clinic. Even though cutting-edge imaging techniques exist to assess these patients, auscultation remains the first-line and fundamental method of evaluating lung sounds. Without question, accurately identifying auscultating breath sounds and then aligning those findings with a general exam and history are keys to true diagnosis. To optimize the health outcomes of patients with respiratory distress symptoms, this article reviews the auscultation of breath sounds in a routine clinical examination.

Background

“Breath sounds” refer to the movement of air through the respiratory system and can be evaluated through auscultation of the lung fields. Auscultation, a technique that requires both clinical experience and a good stethoscope, dates back to the early 1800s. René Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec established the link between a breath sound and an identifiable pathological change in the lungs. During this process, Laënnec invented the stethoscope.

Breath sounds are categorized as normal or abnormal and have 3 characteristics: intensity (soft, medium, loud, very loud), pitch (low, medium, high), and duration. There is often confusion between breath and voice sounds; breath sounds generate in the lungs whereas voice sounds generated in the larynx.

Normal Breath Sounds

Normal breath sounds can be heard throughout the lung fields in a healthy patient and are most often classified as 1 of 4 types: vesicular, tracheal, bron- chosvesicular, and bronchial. In airfilled lungs, vesicular breath sounds are commonly heard over the majority of the lung fields. Tracheal sounds are heard best over the trachea and typically are louder and have a higher pitch than vesicular sounds. Bronchovesicular breath sounds are best heard between the first and second intercostal spaces of the anterior chest. Bronchial sounds are best heard over the body of the sternum.

Abnormal Breath Sounds

Abnormal breath sounds are often indicators of pathology in the airways and include wheezing, crackle, rhonchi, stridor, and plural rub. Because each of these adventitious breath sounds may be present with one or more diagnoses, it is important to make note of the abnormality in context with the patient’s history and clinical exam.

Wheezingis often described as a musical note. The fluctuation of opposing airway walls being tightened nearly to a point of contact generates the sound. A wheeze may occur during either, or both, of the inspiratory and expiratory phases of the respiratory cycle. The timing of an adventitious sound within the respiratory cycle is a diagnostic identifier and should be noted during an exam. Wheezing may be a single sound or a multitude of sounds, and although its presence may be diagnostic for airflow obstruction, its absence does not rule anything out.

Conditions associated with wheezing include viral illnesses such as bronchiolitis, croup, and whooping cough; asthma; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); cystic fibrosis; bronchiectasis; pulmonary edema; foreign body aspiration; or tracheal or laryngeal tumors. Of note, healthy patients can often produce a benign wheeze during forced expiration.

Crackleis an explosive short sound. Unlike a wheeze, it is not musical in nature. Crackles can be categorized as coarse or fine and may occur during either, or both, inspiration and expiration. These sounds are most often heard at the base of the lungs. A fine crackle has an increased frequency rate and quicker duration than a course crackle. Whereas the sudden opening of closed airways triggers a fine crackle, a coarse crackle is associated with the presence of secretions. Conditions associated with crackles include cardiac disease, fibrotic lung disease, COPD, and pneumonia. Regardless of the diagnosis, research has been unable to link disease severity with the quantity of crackles heard on exam.

Rhonchiare low-pitched, continuous, rattling breath sounds that often sound like snoring. They are associated with the presence of secretions, whether increased production or reduced clearance. Typically, rhonchi are cleared when a patient coughs.

Stridoris a high-pitched, unremitting sound heard over the trachea. It tends to occur when the upper airways are narrowed to 5 mm or less and is associated with any condition that leads to narrowing of the extra-thoracic airway. Stridor is louder on inspiration than expiration and much louder than wheezing.

Pleural rubis a harsh, high-pitched sound, such as that which occurs when opposing surfaces are being moved against one another. Some describe the sound as being similar to walking over fresh snow. It is often mistaken for a coarse crackle and occurs when the pleural lining is inflamed and has a deficit of lubrication; such as in pneu- monia, pleurisy, or pulmonary embo- lism. A pleural rub can be localized to a specific area of the lung.

Examining the Patient

Respiratory exams comprise 5 parts, with auscultation being the final com- ponent. A popular pneumonic to re- member this process isPIPPA:

1. Position of the patient

2. Inspection of the patient and his or her respiratory efforts

3. Palpation of the patient’s chest, both anterior and posterior

4. Percussion of the patient’s chest wall

5. Auscultation of the patient’s chest, both anterior and posterior.

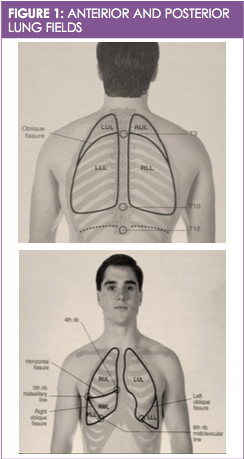

A quiet room and a stethoscope are needed when examining the patient with the intent of auscultating their breath sounds. The diaphragm of the stethoscope should be used for the assessment, and the exam should focus on listening to the anterior, posterior, and mid-axillary regions of the lungs (see Figure 1). The exam should not be conducted over clothing of any kind, regardless of how thin that clothing may be; it should be done in such a manner that the stethoscope has direct contact with the skin.

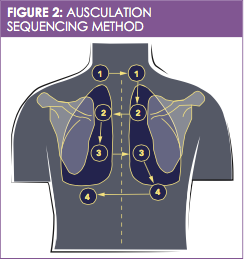

For the purposes of the exam, the anterior, posterior, and mid-axillary regions can be divided into 4 horizontal sections, and the anterior and posterior regions can be further divided into 2 lateral sections (right and left). There are a total of 8 assessment sites on each of the anterior and posterior regions and 4 on each of the mid-axillary regions. For the anterior and posterior exam, the patient’s lungs should be assessed from top to bottom, going left to right in a zigzag manner (see Figure 2). For the mid-axillary assessment, going from top to bottom at each of the 4 sites is recommended. The goal of auscultation is to listen to 1 complete respiratory cycle at each of the sites while paying particular attention to the duration, pitch, and intensity of the breath sounds and comparing them symmetrically.

For the exam, place the patient in an upright, seated position or in a supine position where they can be rolled from one side to another for assessment of the posterior lung fields. The patient should first take a normal breath through their mouth and then a deep breath for the exam.

Auscultating breath sounds may be more difficult to detect in obese patients due to excess adipose tissue diffusing breath sounds. In these cases, correctly positioning the patient will optimize the exam. If decreased or absent breath sounds are identified and the patient is correctly positioned for quality auscultation, a differential diagnosis may include pleural effusion, emphysema, restriction, or obstruction.

Patient Follow-Up

Depending on the outcome of the patient’s exam, abnormal breath sounds may require further testing, such as chest x-ray, chest computerized tomography scan, pulmonary function tests, or sputum sample analysis. Referral to a pulmonary specialist may be warranted if symptoms are severe, chronic, unresponsive to treatment, or not well defined. Encourage the patient to quickly communicate any discomfort they experience during the exam and take immediate note of cyanosis, nasal flaring, difficulty breathing, and acute shortness of breath, as these symptoms may indicate a medical emergency.

Recommended Reading

1. Scherer JR. Before cardiac MRI: Rene Laennec (1781-1826) and the invention of the stethoscope.Cardiology J.2007;14(5):518-519.

2. Sengupta N, Sahidullah M, Saha G. Lung sound classification using cepstral-based statistical features.Comput Biol Med.2016:75:118-129. doi: 10.1016/j .compbiomed.2016.05.013.

3. Gavriely N.Breath Sounds Methodology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1995.

4. Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Murray JF, Nadel JA. History and physical examinations. In: David JL, Murray JF, eds.Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:493-510.

Karen Rance DNP, APRN, CPNP, AE-C, is an allergy, asthma, and immunology specialty nurse practitioner. She is the US Clinical Affairs and Education Liaison with Thermo Fisher Scientific and an adjunct faculty member at Indian Wesleyan University Graduate School of Nursing. Dr. Rance has served on the board of directors of the National Association of Certified Asthma Educators and is on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s National Asthma Education Prevention Program Expert Panel workgroup. She is the founding chair of the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners’ (NAPNAP) Asthma and Allergy Special Interest Group and is on NAPNAP’s Clinical Expert Panel for Asthma.