Influenza: Differential Diagnosis and Treatment

Clinicians should remain abreast of the latest recommendations and strengthen their assessment skills as flu season approaches.

It is that time again: flu season! Starting now, nurse practitioners and physician assistants should prepare for the rush of patients with a variety of clinical presentations. Although influenza is both preventable and treatable, it results in about 200,000 hospitalizations1and 20,000 deaths2per year in the United States. Clinicians should remain abreast of the latest recommendations and strengthen their assessment skills as flu season approaches.

The purpose of this article is to review fundamental information about influenza, with a focus on assessment, differential diagnosis, and treatment. The article concludes with additional resources, patient education, and pertinent ICD-10 codes.

Background

A member of the Orthomyxoviridae family, influenza is a single-stranded RNA virus. Infection is caused by one of 3 types of influenza virus: A, B, or C. Influenza A and B are the most prevalent, whereas influenza C causes a mild infection and does not contribute to seasonal epidemics. Minor genetic variations, also called antigenic drift, result in the variations from season to season. Seasonal variation requires the development of unique vaccines each year.

Prevention

The annual influenza vaccine continues to be the most effective method of reducing infection rates around the world. Administration of the vaccine should be offered by October and continue until April of the following year.3Whereas the vaccine is recommended for everyone older than 6 months, special emphasis should be placed on those with an increased risk for complications, including:

- Children aged 6 months through 4 years

- Adults over the age of 50

- Immunosuppressed individuals

- Women who are or may become pregnant during this flu season

- Children receiving long-term aspirin therapy

- Residents of nursing homes

- American Indians and Alaska Natives

- Morbidly obese individuals4

This flu season, US vaccinations are designed to protect against an A/California/ 7/2009 (H1N1)-like virus; an A/ Switzerland/9715293/2013 (H3N2)-like virus; and a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus.3This represents changes in the influenza A virus compared with last season.

Incidence and Prevalence

Interestingly, the seasonal incidence of influenza varies with latitude. Whereas the flu peaks in the winter in temperate climates, it remains consistent throughout the year in tropical climates.5Each year in the temperate climate of the United States, about 200,000 individuals are hospitalized due to the flu and almost two-thirds of these hospitalizations are among those patients older than 65 years.1Real-time influenza activity in the United States can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) website FluView (cdc.gov/flu/weekly/).

Transmission

The transmission of influenza occurs through large-particle respiratory droplets and fomites. These respiratory droplets can travel about 6 feet and survive on dry, inanimate surfaces for a few days.6Common fomites in a convenient care clinic include skin cells, hair, clothing, chairs, door knobs, pens, and clipboards. The incubation period for influenza is about 48 hours, so it is essential that you follow your clinic’s guidelines for cleaning and disinfecting surfaces.

Assessment

Clinical Presentation

The most common presenting symptoms of influenza include acute onset fever, myalgia, arthralgia, anorexia, headache, dry cough, malaise, fatigue, weakness, and chest discomfort. Symptoms of severe or progressive influenza infection include altered mental status, seizures, hypoxia, tachypnea, and decreased urine output. Due to overlap of influenza symptoms with other illnesses, a clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by a laboratory test (see “Diagnostic Tests” below).7

Physical Exam

In general, clinicians should assess for fever, myalgia, arthralgia, cough, pharyngitis, and rhinorrhea.8Flushing may be seen on the face and the skin may be hot, dry, or diaphoretic. Rhonchi or scattered rales may be heard upon auscultation of the lungs. Other findings might include conjunctival injection, pain on eye motion, photophobia, and nonexudative pharyngitis.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Upper respiratory infections (URIs) and infectious mononucleosis are frequently confused with influenza. Influenza typically has an acute onset with high fever, headache, dry cough, and achy muscles and joints. In comparison, URIs have a more gradual onset, productive cough, and no fever. Infectious mononucleosis presents with characteristic posterior cervical lymphadenopathy.Table 17-10and theFiguresummarize the key differences.

Diagnostic Tests

Clinicians should consider a diagnostic test if influenza is suspected based on the clinical presentation and physical exam.7Commonly used diagnostic tests for influenza include rapid antigen detection testing, reverse transcriptase- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and viral culture. Rapid antigen detection tests provide the quickest results; however, the sensitivity of this test is generally low and does not exclude influenza in a symptomatic patient.11An RT-PCR test is the most sensitive and specific test for influenza and can be especially helpful for differentiating between influenza types A and B.12Viral cultures can be used to confirm a diagnosis of influenza; however, they are more frequently used for surveillance during viral outbreaks.12

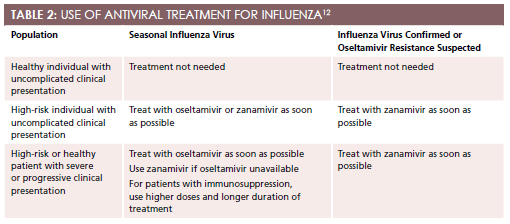

Antiviral treatment is not needed for healthy individuals with an uncomplicated clinical presentation.13This treatment is recommended for any individual with known or suspected influenza who is hospitalized, at a high risk for complications, or who presents with a severe, progressive illness.Table 212summarizes World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for the use of antiviral treatment for influenza.

If indicated, start antiviral therapy as soon as possible, ideally within 48 hours of symptom onset. There are 2 classes of anti-influenza medications: adamantanes and neuraminidase inhibitors. Neuraminidase inhibitors are recommended as first-line treatment.Table 312includes specific dosing information. Adamantanes are no longer recommended for treatment due to widespread resistance since the 2005- 2006 flu season.14

Additional Information

Clinician Resources

A multitude of clinical resources are available for influenza treatment information. Among these are the CDC’sMorbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which provides detailed recommendations for the 2015-2016 flu season3; the Department of Health and Human Services website flu.gov, which offers updates on current flu outbreaks across the country; and the CDC’s FluView, which provides weekly geographic updates. Additionally, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) publishes a point-ofcare guide for diagnosing and treating adults with suspected influenza,15 and the Clinical Infectious Diseases journal provides an updated review of influenza virus resistance to antiviral agents.16

Patient Education

A variety of reputable organizations provide free influenza patient education. Both the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic offer printable handouts appropriate for all educational levels. The AAFP also provides useful patient information in both English and Spanish. Finally, Patient Plus, a social network connecting health care providers with their patients, has created a handout for patients who are interested in learning technical information about the flu.

ICD-10 Codes

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD- 10), the updated coding system for disease classification developed by WHO, was recently adopted in the United States after years of postponement. Compared with the previous coding system, ICD-10 codes provide greater specificity and diagnostic detail. For more information on the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10, check out theContemporary Cliniconline articles, “Appreciating the Big Picture of ICD- 10” and “The ICD-10 Transition: What You Need to Know.”

Here is a selection of influenza-related codes17:

- J09: influenza due to certain identified influenza virus

- J10: influenza due to other identified influenza virus

- J10.0: influenza with pneumonia, other influenza virus identified

- J10.1: influenza with other respiratory manifestations, other influenza virus identified

- J10.8: influenza with other manifestations, other influenza virus identified

- J11: influenza, virus not identified

- J11.0: influenza with pneumonia, virus not identified

- J11.1: influenza with other respiratory manifestations, virus not identified

- J11.8: influenza with other manifestations, virus not identified

Melissa DeCapua, DNP, PMHNP, is a board-certified psychiatric nurse practitioner who graduated from Vanderbilt University. She has a background in child and adolescent psychiatry, as well as psychosomatic medicine. Dr. DeCapua currently works as the Healthcare Strategist at a Seattle-based health information technology company where she guides product development by combining her clinical background and creative thinking. She is a strong advocate for empowering nurses, and she fiercely believes that nurses should play a pivotal role in shaping modern health care.For more about Dr. DeCapua, please visit melissadecapua.com or follow her on Twitter @melissadecapua.

References

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States.JAMA. 2004;292(11):1333-1140.

- Foppa IM, Hossain MM. Revised estimates of influenza-associated excess mortality, United States, 1995 through 2005.Emerg Themes Epidemiol.2008;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-26.

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Olsen SJ, Bresee JS, Broder KR, Karron RA. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2015-16 influenza season.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2015;64(30);818-825.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination: who should do it, who should not and who should take precautions. www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/whoshouldvax.htm. Updated November 4, 2015. Accessed November 6, 2015.

- Viboud C, Alonzo WJ, Simonsen L. Influenza in tropical regions.PloS Med.2006;3(4):e89. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030089.

- Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review.BMC Infect Dis.2006;6:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-130.

- Call SA, Vollenweider MA, Hornung CA, Simel DL, McKinney WP. Does this patient have influenza?JAMA.2005;293(8):987-997.

- Montalto NJ. An office-based approach to influenza: clinical diagnosis and laboratory testing.Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(1):111-118.

- Simasek M, Blandino DA. Treatment of the common cold.Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):515-520.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis [published correction appears inN Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1486].N Engl J Med.2010;362(21):1993-2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001116.

- Chartrand C, Leeflang MM, Minion J, Brewer T, Pai M. Accuracy of rapid influenza diagnostic tests: a meta-analysis.Ann Intern Med.2012;156(7):500-511. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00403.

- Harper SA, Bradley JS, Englund JA, et al; Expert Panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Seasonal influenza in adults and children—diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2009;48(8):1003-1032. doi: 10.1086/598513.

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for pharmacological management of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza and other influenza viruses. www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/h1n1_use_antivirals_20090820/en/. Published February 2010. Accessed October 21, 2015.

- Jefferson T, Jones MA, Doshi P, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children. Cochrane database syst rev. 2014;10(4). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008965.pub4

- Ebell MH. Diagnosing and treating patients with suspected influenza.Am Fam Physician.2005;72(9):1789-1792.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Ovsyannikova IG. Influenza virus resistance to antiviral agents: a plea for rational use.Clin Infect Diss. 2009;48(9):1254-1256. doi: 10.1086/598989.

- ICD-10 Version: 2015. World Health Organization website. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en#/J09-J18.