Collaborative Obesity Management: Advanced Practice Clinicians Working with Patients

Over the last 2 decades, obesity has reached epidemic proportions.

Over the last 2 decades, obesity has reached epidemic proportions.

Introduction

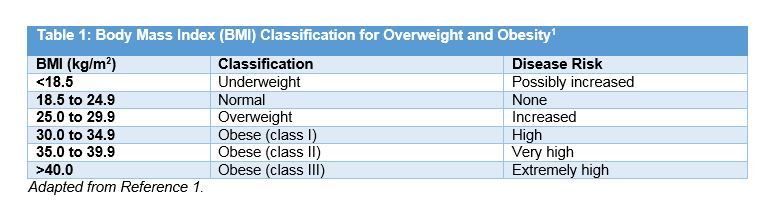

Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) is the standardized measure used to define obesity (Table 1).1In the United States, 1 in 3 adults is obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and another 1 in 3 adults is overweight (BMI ≥25 but <30 kg/m2).2

Obesity has recently been classified as a disease by the American Medical Association.3Clinic visits to provide obesity counseling and behavior modification are reimbursed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as follows: 1 face-to-face visit every week for a month, 1 visit every other week during months 2 through 6, and 1 visit during each remaining month through 1 year if the patient loses at least 3 kg during the first 6 months of treatment.4

Obesity is a risk factor for the development of a number of comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, reduced fertility, and sleep apnea, and an increase in the prevalence of certain cancers.5The risk of developing these complications is directly related to the degree of obesity.6A modest weight loss of as little as 3% to 5% of baseline weight has been associated with improvement in cardiometabolic risk factors such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. However, it is generally recommended that an initial weight-loss goal of 10% should be achieved over the first 6 months of treatment.7After 6 months, the rate of weight loss usually declines due to a decrease in energy expenditure at the lower weight.

Management Strategies

8

A combination of diet, exercise, and behavior modification is the foundation of obesity prevention and weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese.In addition, the use of adjunctive drug therapy may be considered in patients with a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2and an obesity-related comorbidity or a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2.9Bariatric surgery is an option in patients with a BMI of at least 40 kg/m2or a BMI of at least 35 kg/ m2who have an obesity-related comorbidity despite a comprehensive treatment strategy including diet, exercise, and pharmacologic therapy.8

Counseling patients about weight loss can be a sensitive issue. The initial discussion about obesity and weight loss can be the most difficult. It is generally recommended to follow the 5 As (Ask, Assess, Advise, Agree, Arrange/Assist), most notably used in the setting of smoking cessation.10,11Once a patient is willing to discuss weight loss, a number of factors must be considered, including health status, age, culture, and health literacy. Avoid telling patients what to do, as most already know what is recommended, (e.g., eat less and exercise more). What patients need is help with how to do these things. Listen to the patients’ concerns and offer encouragement.

Diet

For an overweight patient with a BMI of 27 kg/m2to 35 kg/m2, a calorie deficit of 300 to 500 kcal per day typically results in weight loss of about 0.5 to 1 lb per week and a 10% weight loss in 6 months.1For a patient with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, deficits of 500 to 1000 kcal/day typically result in weight loss of approximately 1 to 2 lb per week and a 10% weight loss in 6 months.1It is acceptable to restrict certain food groups when following a low-fat, low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet. It is also acceptable to follow commercial diet plans which feature a low-carbohydrate, moderate macronutrient, or low-fat dietary intake.12There is evidence that all of these nutrition plans can be effective in promoting weight loss, with relatively small differences in the amount of weight lost between the plans. The key is to find the diet plan that is palatable to the patient. A nutrition plan that patients can follow long-term is the most important determinant of success.

Exercise

Physical activity is an important component of a comprehensive weight-loss strategy. Exercise alone is typically not associated with substantial weight loss. However, exercise does decrease abdominal fat, increase cardiorespiratory fitness, and is important for the maintenance of weight loss once it occurs. The recommended amount of exercise is 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week (30 minutes per session, 5 times a week).13Alternative strategies incorporating more vigorous aerobic activity for shorter periods of time may require the input of an exercise specialist and are less likely to be readily achieved by the majority of patients. Patients may start with as little as 10 minutes of aerobic exercise per day. With repetition over time, they should be able to develop the stamina to exercise in 30-minute increments.

In addition to aerobic exercise, muscle-strengthening activity is recommended twice a week for all major muscle groups.13The exercise prescription should be individualized based on the ability of the patient. Some patients may need nonweight-bearing activity (swimming, water aerobics, stationary bicycle) to achieve the desired exercise end point. Exercise prescriptions are typically provided in the FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type) format.

Behavior Modification

For a patient to lose weight, dietary and physical activity behavior patterns must change. However, behavior modification also includes the following: identifying behavior change goals; reviewing when, where, and how behaviors will be changed and how those changes will be integrated into the activities of daily living; and keeping records of behavior (food and physical activity logs; journaling to identify times where craving, stress, and coping skills were employed).7Progress based on patients’ personal records of behavior as well as changes in weight, blood pressure, heart rate, blood glucose, and other metabolic parameters should be reviewed at each follow-up visit.

Pharmacotherapy

Drug therapy as an adjunct to lifestyle modification has not been shown to improve long-term clinical outcomes. A number of weight-loss drugs (eg, fenfluramine, dexfenfluramine, sibutramine) have been removed from the market due to adverse cardiovascular outcomes.9A few centrally acting amphetamine-like anorectic agents remain on the market. These drugs are only recommended for short-term use (12 weeks). Longer durations of use of these drugs as monotherapy would be expected to increase adverse cardiovascular outcomes. These drugs also have the potential for the development of tolerance and addiction. The current recommendation concerning the use of weight-loss drugs in the management of obesity is that the benefit—risk profile of these drugs must be favorable for long-term use (Table 29,17-19,21).9,14

Orlistat (Xenical)

Orlistat is a peripherally acting pancreatic lipase inhibitor that reduces absorption of fat from the intestine and is associated with modest weight loss.15It has been evaluated in a 4-year study with an average weight loss of about 6 kg compared with 3 kg with placebo.16Its most common adverse effect (AE) is steatorrhea, which manifests as oily spotting, flatus with discharge, fecal urgency, fatty/oily stool, oily evacuation, increased defecation, and fecal incontinence.15These gastrointestinal (GI) AEs improve if patients reduce the amount of fat in their diet.

Orlistat may impair the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and can reduce the absorption of fat-soluble drugs such as amiodarone and cyclosporine. Patients taking orlistat should take a multivitamin containing fat-soluble vitamins. In addition, patients taking amiodarone or cyclosporine should take these drugs 2 hours prior to or 4 hours after a dose of Orlistat, which can be difficult to do, given that orlistat is taken 3 times daily with meals.

Since 2012, 4 additional weight-loss products have been approved by the FDA. All of these drugs have been shown to produce significantly more weight loss than placebo. None of these agents has been compared with the others, however, so it is not possible to reach conclusions about their relative effectiveness. The average weight loss from using these agents has been between 6% and 10% of baseline body weight at the end of a year of therapy. The decision to choose one of these agents over another is probably more dependent on an individual drug’s adverse reaction and drug interaction potential.

Phentermine/Topiramate-Extended Release (ER) (Qsymia)

Phentermine/topiramate-ER is thought to suppress appetite through the central nervous system. The exact mechanism of topiramate for this indication is unknown.17It was originally approved as an anticonvulsant and for migraine prophylaxis. Treatment is started with phentermine 3.75 mg/ topiramate 23 mg ER taken once a day in the morning (to avoid insomnia with phentermine) with or without food for 2 weeks. On the 15th day, the dose is increased to 7.5 mg/46 mg ER once in the morning. If patients do not lose at least 3% of baseline body weight after 12 weeks on this “standard” maintenance dose, the drug should either be discontinued or the dose increased to 11.25 mg/69 mg ER once daily for an additional 14 days. On the 15th day of this intermediate dose, 15 mg/92 mg ER should be started. If patients have not lost at least 5% of body weight after 12 weeks on the “high” maintenance dose, the drug should be discontinued. Patients successfully completing a year of therapy on either maintenance dose saw significant improvements in waist circumference, blood pressure, blood glucose, and dyslipidemia.

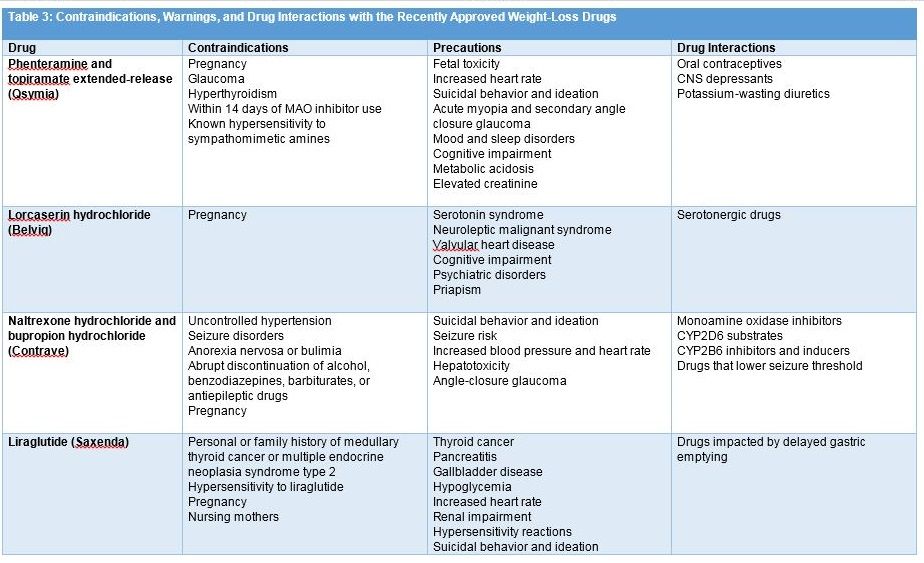

The most commonly reported AEs with this product are paresthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, constipation, insomnia, and dysgeusia.17Contraindications and warnings concerning the use of phentermine/topiramate-ER are summarized inTable 3.17-19,21Patients titrated to the maximum dose of 15 mg/92 mg who must discontinue therapy should reduce the dose gradually prior to discontinuation to lessen the risk of seizure by taking a dose every other day for 1 week prior to discontinuation.

Due to the topiramate component, phentermine/topiramate-ER may cause fetal harm. Topiramate is associated with a 2- to 5-fold increase in the incidence of oral clefts in fetuses exposed to the drug during the first trimester of pregnancy. Due to this risk of teratogenicity, women of childbearing potential should take a pregnancy test prior to starting phentermine/topiramate-ER and then retest every month for the duration of therapy.17Women should be counseled concerning the use of effective contraception during therapy. Should pregnancy occur during the use of phentermine/ topiramate-ER, the drug should be discontinued immediately. The drug should also be avoided in women who are breastfeeding. The FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy for phentermine/topiramate-ER due to its risk of teratogenicity, which limits its distribution to certified pharmacies.

Lorcaserin (Belviq)

Lorcaserin is a selective 5-HT2C agonist thought to promote weight loss via appetite suppression.18The drug is dosed at 10 mg twice daily with no need for dose titration. If a weight loss of at least 5% compared with baseline is not achieved after 12 weeks of treatment with the twice daily 10-mg dose, the drug should be discontinued. Lorcaserin has an uncomplicated dosing regimen (one dose for all patients) with no dosage adjustments recommended in any subgroup of patients. In patients with mild renal impairment, no dose adjustment is required. For patients with moderate renal dysfunction, caution with the use of lorcaserin is recommended. For patients with severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease, lorcaserin is not recommended. No dosage adjustment is required for patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic dysfunction, but the drug is not recommended in patients with severe hepatic impairment. The most common AEs that occur with lorcaserin include headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, dry mouth, and constipation.18Contraindications and warnings are summarized in Table 3.17-19,21

Naltrexone (Contrave) / Bupropion

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, appears to have only a minimal effect on weight loss when used alone. Bupropion reduces food intake by stimulating dopamine receptors in the hypothalamus. Combining naltrexone with bupropion is thought to inhibit the effects of beta-endorphin release associated with dopamine receptor stimulation, potentiating the effects of bupropion on food intake.19The drug is available as a fixed-dose combination of a sustained-release formulation of 8 mg naltrexone/90 mg bupropion.

The drug is initiated at a dose of 1 tablet in the morning once daily for 1 week, followed by 1 tablet in the morning and one in the evening each day for 1 week, followed by 2 tablets in the morning and 1 tablet in the evening for 1 week, followed by a maintenance dose thereafter of 2 tablets in the morning and 2 in the evening daily (32 mg naltrexone/360 mg bupropion). If patients fail to achieve weight loss of at least 5% after 12 weeks on the 2-tablet twice-daily maintenance dose (total of 16 weeks on bupropion/naltrexone), the drug should be discontinued.19

No dosage guidance is available for patients with mild renal impairment. In patients with moderate to severe renal impairment, the maximum dose is 1 tablet twice daily. The drug is not recommended in patients with end-stage renal disease. In patients with moderate to severe hepatic dysfunction, the recommended dose is 1 tablet daily.

The most frequent AEs with naltrexone/ bupropion include nausea, headache, vomiting, dizziness, insomnia, dry mouth, and constipation.19Contraindications and warnings are summarized in Table 3.17-19,21

Liraglutide (Saxenda)

Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor antagonist originally approved for the treatment of T2D (Victoza). Studies evaluating the use of liraglutide for the management of obesity used a higher dose than that approved for diabetes. The recommended maintenance dose of liraglutide for diabetes is 1.2 mg or 1.8 mg administered subcutaneously (SC) once a day based on glycemic response.20The target maintenance dose of liraglutide for obesity is 3.0 mg SC once a day.21Liraglutide is administered SC in the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm at any time of the day without regard for meals. The drug is initiated at 0.6 mg daily for 1 week. The dose is titrated at the start of the second week to 1.2 mg per day. Each subsequent week the daily dose is titrated to 1.8 mg, then 2.4 mg, and finally 3.0 mg. If, after 12 weeks on the recommended maintenance dose of 3.0 mg daily, the patient has not lost at least 4% of body weight, the drug should be discontinued.

Patients taking insulin secretagogues for diabetes should reduce the dose of those drugs by one-half at the start of liraglutide therapy.21Patients missing a dose of liraglutide should resume the drug with the next scheduled dose. Patients missing more than 3 days of liraglutide therapy should reinitiate therapy at the 0.6-mg-per-day dose and follow the initial titration schedule.

Liraglutide solution is available as a disposable, prefilled, multidose pen. Victoza and Saxenda contain the same concentration of liraglutide (6 mg/ml), but the pens are calibrated differently. The maximum dose that can be delivered with the Victoza pen is 1.8 mg, while the Saxenda pen can deliver doses of 2.4 mg (titration step) and 3.0 mg. Hence, the 2 pens are not interchangeable.

The most common AEs reported with Saxenda are GI disorders. In clinical trials, 9.8% of patients discontinued Saxenda compared with 4.3% with placebo. The most common AEs leading to drug discontinuation included nausea (2.9%), vomiting (1.7%), and diarrhea (1.4%).21 Contraindications and warnings with the use of liraglutide are shown in Table 2.9,17-19,21

Conclusion

A combination of diet, exercise, and behavior modification is the foundation of obesity prevention and weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese.7,8Weight-loss drug therapy has been shown to improve some obesity-related complications, especially glycemic control and blood pressure. However, it is well documented that after patients discontinue weight-loss drug therapy, weight regain is inevitable.9Among prescribers and patients choosing to use adjuvant drug therapy, the hope is that patients will be able to discontinue drug therapy at some point and maintain weight loss through adherence to lifestyle changes alone. However, there is no long-term evidence that this approach can be successfully implemented in large numbers of patients.

The long-term safety of the newer weight-loss drugs is unknown.22No weight-loss drug has ever been demonstrated to reduce cardiovascular morbidity or mortality, but all weight-loss drugs have the potential for toxicity and require monitoring. Until the results of long-term outcomes trials are available, the use of the current FDA-approved drugs will continue to be associated with an unknown benefit—risk profile.22

Support from family and/or friends, as with all health-related behavioral changes, is an important part of a comprehensive treatment program. Communication between the caregiver and patients and patients’ family and/or friends should address available resources in the community. In the case of obesity, that communication should focus on resources specifically related to healthy nutrition and physical activity.23

Daniel E. Hilleman received his PharmD degree from Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska. He completed a predoctoral research fellowship at the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital in Omaha. Dr. Hilleman joined the faculty at the Creighton University School of Pharmacy in 1981. In 1985, Dr. Hilleman was appointed director of clinical research at the Creighton University Cardiac Center and held that position until 1993, when he was appointed chair, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions. Dr. Hilleman stepped down as chair in 2004 and has been practicing in cardiology and critical care at Creighton University’s teaching hospital. In 2012, Dr. Hilleman was appointed director of continuing education for the Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions.

Syed M. Mohiuddin, MD, is a professor of medicine in Division of Cardiology and the Department of Internal Medicine at the Creighton University School of Medicine in Omaha, Nebraska. Dr. Mohiuddin received his MD degree from Osmania University in India. His postgraduate training was primarily at Creighton University School of Medicine in Omaha, Nebraska, and the Universite’ Laval in Quebec, Canada. He holds a DSc in medicine from the Universite Laval. His primary research interests are cardiovascular pharmacology and non-invasive diagnostic techniques in cardiology.

References

- NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1998. NIH publication 98-4083. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/ob_gdlns.pdf. Published September 1998. Accessed September 15, 2015.

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010.JAMA. 2012;307(5):491-497.

- AMA adopts new policies on second day of voting at annual meeting [press release]. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; June 18, 2013. www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/news/news/2013/2013-06-18-new-ama-policies-annual-meeting.page Accessed September 21, 2015.

- Intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) for obesity. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM7641.pdf. Updated March 9, 2012.

- Malnick SD, Knobler H. The medical complications of obesity.QJM. 2006;99(9): 565-579.

- National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Overweight, obesity, and health risk.Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(7):898-904.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2985-3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004.

- Kushner RF. Weight loss strategies for treatment of obesity.Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56(4):465-472. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.005.

- Bray GA, Ryan DH. Medical therapy for the patient with obesity.Circulation. 2012;125(13):1695-1703. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026567.

- Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling-Turer CL, et al. Do the five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss?Fam Med. 2011;43(3):179-184.

- Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM, Freedhoff Y. Modified 5 As: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care.Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(1):27-31.

- Johnston BC, Kanters S, Bandayrel K, et al. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis.JAMA.2014;312(9):922-933. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10397.

- How much physical activity do adults need? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/index.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Colman E. Food and Drug Administration's obesity drug guidance document: a short history.Circulation. 2012;125:2156-2164. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028381.

- Xenical [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc; 2015. www.gene.com/download/pdf/xenical_prescribing.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2015.

- Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjostrom L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients.Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):155-161. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.155.

- Qsymia [package insert]. Mountain View, CA: Vivus, Inc; October 2014. Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Belviq [package insert]. Zofingen, Switzerland: Arena Pharmaceuticals GmbH; August 2013.Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Contrave[package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Inc; 2014.Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Victoza[package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ; Novo Nordisk; 2010. Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Saxenda[package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; December 2014. Accessed September 16, 2015.

- Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. The new weight loss drugs, lorcaserin and phentermine-topiramate: slim pickings?JAMA Int Med. 2014(4);174:615-619. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14629.

- Dietz WH, Solomon LS, Pronk N, et al. An integrated framework for the prevention and treatment of obesity and its related chronic diseases.HealthAffairs (Millwood). 2015;34(9):1456-1463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0371.